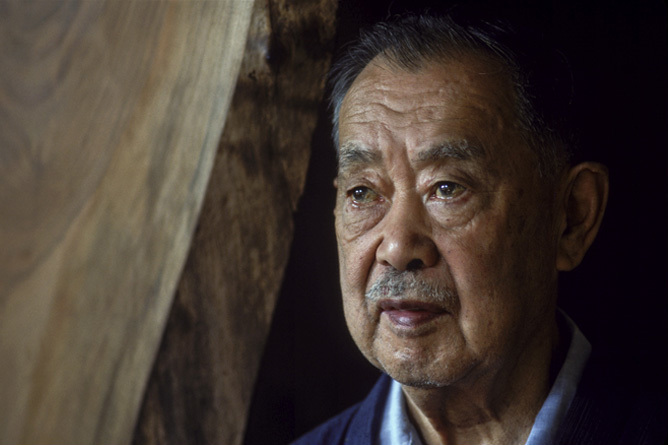

George Nakashima credited a dark chapter in our nation’s history for his success as one of the twentieth century’s greatest furniture designers. Born in Spokane, Washington, the child of Japanese immigrants and descendants of samurai, Nakashima first studied forestry but later earned degrees in architecture from the University of Washington and MIT. After receiving his Masters, he sold his car, bought a round-the-world steamship ticket and traveled around the globe seeking inspiration. First came a year in France, then a visit to North Africa and two years in an Indian ashram. He landed finally in Japan, where he immersed himself in Japanese culture.

In Tokyo, he met the American architect Antonin Raymond, Frank Lloyd Wright’s chief assistant on his Imperial Hotel. Nakashima was hired by Raymond and gained his first experience designing furniture on a dormitory project. He also met Marion Okajima, like him an American of Japanese heritage, and they soon married.

With the threat of war looming, the young couple returned to the United States in 1940 and started a small furniture workshop in Seattle. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Nakashima, his wife, and baby daughter were rounded up and forced into an internment camp, like 100,000 other Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast. The family was sent to the Minodoka War Relocation Center in Idaho. Years later, many internees would remember these lost years with justifiable sadness and bitterness. Despite being loyal Americans, they were taken from their homes and imprisoned without trials or due-process. But George Nakashima remembered these years differently.

- Newspaper headlines announcing Japanese American relocation. February 1942.

- Japanese-American internees in Idaho at the Minidoka War Relocation Center

- Nakashima at work

In this isolated desert camp, Nakashima met a traditional Japanese craftsman in his forties, Gentaro Hikogawa, a meeting that would change his life. The man became his master and trained the young architect in traditional Japanese wood-working tools and techniques. For Nakashima, the Idaho camp’s unhurried pace, isolation, and peaceful existence were essential to his mastering the craft of furniture making.

Hikogawa stressed the importance of patience and reaching for perfection. Nakashima, who had once studied forestry, recognized a natural combination between ancient wood-working techniques and respect for the spirit of the tree. For him, furniture making was a partnership and his role was to provide the tree with ‘new life.’

In 1943, Antonin Raymond convinced government officials to release Nakashima and his family, acting as their sponsor and arranging for him to work at Raymond’s studio in New Hope, Pennsylvania. His plan was to create a studio that combined the practices of the International School of architecture with traditional Japanese techniques.

- Conoid bench

- Home

- Wood with chalk markings

- Coffee table

- Butterfly joints mend splits

- Home

- Coffee table

- Desk

- Nakashima & conoid chairs

After the end of World War II, Nakashima established his own furniture studio in New Hope and became world-famous as one of the fathers of the American Crafts Movement. Each piece of furniture was finished by hand and custom designed to reflect each commission and the unique quality of the wood. Today, his work is in private collections, like the Rockefeller family’s, and many museums, including the Metropolitan Museum, the Philadelphia Museum, and Morikami Museum. In 1983, he was declared a “sacred treasure” by the Emperor of Japan.

His philosophy of furniture making is best expressed in his own words: