Around 1960, a small boy who liked to explore nature without a map was wandering in the forest near his village. He was frightened when he accidentally discovered the entrance to a cave in the woods. Later, he got up the courage to return alone from his house with a lantern. His decision to explore the cave’s passageways would take on greater meaning in the years to come.

Around 1960, a small boy who liked to explore nature without a map was wandering in the forest near his village. He was frightened when he accidentally discovered the entrance to a cave in the woods. Later, he got up the courage to return alone from his house with a lantern. His decision to explore the cave’s passageways would take on greater meaning in the years to come.

The boy was Shigeru Miyamoto and he grew up to be one of the founding fathers of electronic game design. As a young man, he wanted to be a manga artist and went to college for art and design. After graduation, his father got him an interview at an old Japanese company that specialized in playing cards, but had begun to expand its offerings into electronic toys – Nintendo. Miyamoto brought children’s clothes hangers in the shape of animals that he had designed and convinced the company to hire its first artist.

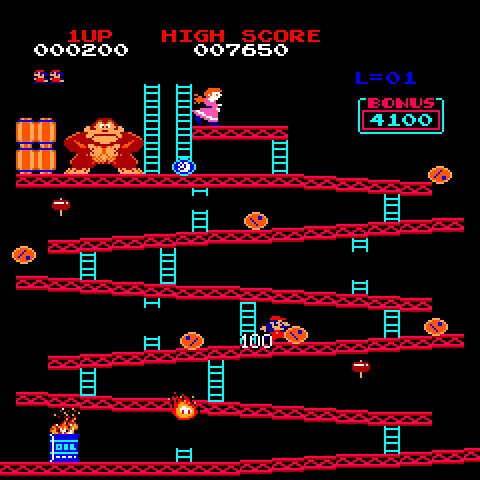

A couple of years later, motivated by the huge success of video arcades, Nintendo built their own version of Space Invaders that failed dismally. Stuck with two thousand unsold arcade units, they turned to their artist and asked if he could come up with a better game. At this time, video arcades games, while popular, were little more than shapes shooting and attacking other shapes. But in 1982 that all changed when Nintendo released Miyamoto’s Donkey Kong. Donkey Kong was the first arcade game with a story and characters – a gorilla, the girl he kidnapped but loved, and a hero – a carpenter known in this game as “Mr. Video,” later “Jumpman,” and finally, “Mario” (named for the landlord of Nintendo’s warehouse in Seattle, Washington).

A couple of years later, motivated by the huge success of video arcades, Nintendo built their own version of Space Invaders that failed dismally. Stuck with two thousand unsold arcade units, they turned to their artist and asked if he could come up with a better game. At this time, video arcades games, while popular, were little more than shapes shooting and attacking other shapes. But in 1982 that all changed when Nintendo released Miyamoto’s Donkey Kong. Donkey Kong was the first arcade game with a story and characters – a gorilla, the girl he kidnapped but loved, and a hero – a carpenter known in this game as “Mr. Video,” later “Jumpman,” and finally, “Mario” (named for the landlord of Nintendo’s warehouse in Seattle, Washington).

Bluto, Popeye, and Olive Oyl.

Miyamoto had been inspired by the characters in the Popeye cartoons (Bluto, Olive, and Popeye). Nintendo even tried to license the characters for the game but were turned down. Forced to come up with his own characters, Miyamoto mixed Popeye’s classic plot structure of a villain in love, a damsel in distress and the hero who could save her with the story of King Kong.

Donkey Kong, 1981

In that era of video arcade games, to create something resembling a character required ingenuity. With the handful of pixels available, Miyamoto gave Mario a red hat so you could see his head and a mustache so it could define his nose.

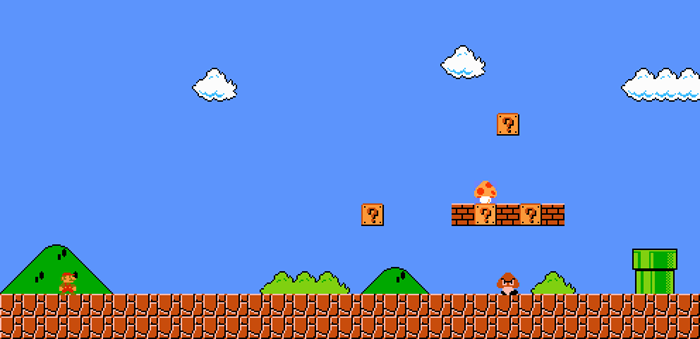

As video game technology improved, Miyamoto was able to increase not only the complexity of character designs (allowing Mario to become a plumber) but the games themselves. While movements in Donkey Kong tend to be up and down, when Mario got his own game it introduced side-scrolling from left to right, based on the way traditional Japanese paint scrolls tell stories.

As video game technology improved, Miyamoto was able to increase not only the complexity of character designs (allowing Mario to become a plumber) but the games themselves. While movements in Donkey Kong tend to be up and down, when Mario got his own game it introduced side-scrolling from left to right, based on the way traditional Japanese paint scrolls tell stories.

Initial screen of Super Mario Bros., 1985

Even in his early days as a game designer, Miyamoto thought a great deal about how to introduce a player to the rules of a new game naturally. For example, in Super Mario Bros., we first see Mario on the left side of the screen, with the right side wide open. This hints to the player to move him to the right. In all later screens, Mario appears at the center. Barriers appear early in the first level, forcing you to find a way to jump and bump into blocks overhead. Players quickly learn how Mario gets stronger. While the game play would continue to evolve, Miyamoto never wanted players to have to depend on a manual.

In 1986, Nintendo moved beyond the arcade and introduced their first home system – in Japan, the Family Computer, but in the West, the NES or Nintendo Entertainment System. Their timing couldn’t have been worse. The home video game console industry was collapsing. While there had been huge demand, too many console companies and too many buggy games had led to a dramatic drop in sales. The leader, Atari, was on the verge of bankruptcy.

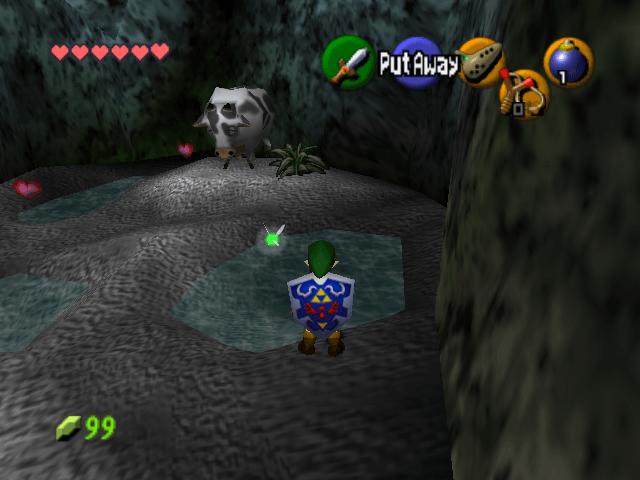

Legend of Zelda, 1986

The Japanese version of the NES console came with a new game called The Legend of Zelda which single-handedly saved the console market and introduced a whole new vision of what a game could be. Like the young boy who once explored a cave, Zelda’s hero, Link, goes on a quest that can take him down many paths. His journey is one of imagination and was the first step in what became known as the “massive exploration adventure.” It also was the first game with a memory chip that could save your place in the game when you left it.

Cave in “Legend of Zelda – Ocarina of Time,” 1998.

Later versions of the Zelda and Mario franchises introduced many technological innovations to electronic games, like a 3D universe. But Miyamoto is not excited by the ability to increase realism or making video games that resemble movies. “I am not convinced that being more realistic makes better games….We have to pursue something that movies cannot do.” In addition to the games themselves, he has played a leading role in the design of consoles and controllers. For the Wii, the first wireless motion capture system, he said, “Our goal was to come up with a machine moms would want.”

Miyamoto’s philosophy has remained remarkably consistent — “The most important thing is for games to be fun.” His games are ones that anyone can play. So in a Mario game “simply put, you run, you jump, you fall, you bump into things. Things that all people do.” In the end, Miyamoto believes that all players should finish with a sense of accomplishment. He wants each player to be a hero. His journeys are ones of imagination, rather than through killing fields. Adventures should not only immerse their players in fantastic environments but allow them to stray from the mission and, as he did as a boy entering a cave, simply explore.

Miyamoto is proud that he creates trends and is not influenced by them. It is no wonder that when the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences created its Hall of Fame, the first person inducted was Shigeru Miyamoto. The Academy’s citation simply states that his peers describe him as “the greatest video game designer in the world.”

What is the secret of his success? Could it be that he never forgot that small boy who found the courage to enter a cave? Miyamoto has said,

What is the secret of his success? Could it be that he never forgot that small boy who found the courage to enter a cave? Miyamoto has said,

“I think inside every adult is the heart of a child. We just gradually convince ourselves that we have to act more like adults.”

Thanks to him, millions have rediscovered the child inside themselves and taken incredible journeys.