Ivan Sutherland and his robot crawler, 1983

In 1982, Ivan Sutherland got on a six-legged walking robot he had built and took his first ride. His students at Carnegie Mellon Institute called the eight foot long machine “The Trojan Cockroach.” To Sutherland it was as an “electric animal,” which he made because he thought it would be fun. Fun has always been Sutherland’s inspiration.

When denied my minimum daily adult dose of technology, I get grouchy. I believe that technology is fun, especially when computers are involved, a sort of grand game or puzzle with ever so neat parts to fit together. I have turned down several lucrative administrative jobs because they would deny me that fun. If the technology you do isn’t fun for you, you may wish to seek other employment. Without the fun, none of us would go on.”

The Trojan Cockroach was the first computer controlled robot that could carry a human being. But it is merely a footnote in the life of the man known as “Father Ivan,” since he is the person who gave birth to computer graphics and who, along with his many students, helped usher in the Computer Age.

Sketchpad

Sketchpad demonstrated in 1963.

Computer graphics was born in 1962. Its twenty-four year old father, Ivan Sutherland, was then a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and his child, who he named Sketchpad, was his doctoral thesis. Sutherland’s program for MIT’s TX2 computer enabled him to draw directly on its nine-inch cathode ray tube with a light pen. For the first time in history, digital images were created by hand and appeared as the artist was working on them (rather than in a printout hours later).

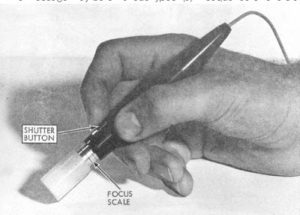

Sketchpad’s light pen.

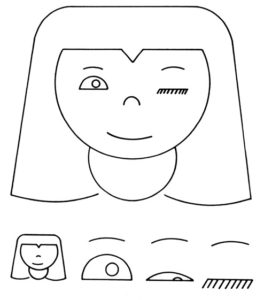

Thus Sketchpad was the first born of the digital media. It utilized a vector system where points are placed on the screen and the software creates the lines between them — the basis of all future vector drawing programs. Though never seen before 1962, much of how Sketchpad operated would be familiar to anyone working in computer graphics today. Keyboard commands allowed him to copy parts of his objects, move them, and delete them. Parts of any image could be resized independently from the rest of the image. Shapes could be shrunk to the size of a dot, copied over and over again to make a pattern, and then enlarged again with no loss of clarity. There were dials below the screen for zooming in or out. It even could be used to create simple animations.

Sketchpad animation: Winking girl, “Nefertite,” and her component parts.

The width of the TX-2’s small screen was treated by Sutherland’s program as a “window,” so when one zoomed in on a form its outer parts would go beyond the edges of the screen. The software also was able to save the images created on the screen for later use. Most of the pioneers of digital media were inspired by Sutherland’s Sketchpad, particularly by the concept that a computer could be designed for use by ordinary people and artists, rather than remain the domain of a select group of technology experts.

Born in Hastings, Nebraska in 1938, Ivan Sutherland was probably the only high school student in the 1950s who had a computer to play with. His engineer father had borrowed it from work. SIMON, a mechanical relay based computer, was so “powerful” that it was capable of adding all the way up to 15. More importantly, it could be programmed—by punching holes into paper tape and then feeding that into a tape reader. Young Ivan’s first program “taught” SIMON to divide, requiring eight-feet of tape.

As a graduate student in engineering at MIT, Sutherland once again had the luck to be one of the few young people in the nation to have a computer available for his research. And this one was much higher powered than SIMON. MIT’s TX-2 had been built for the Air Force to demonstrate that small transistors could replace vacuum tubes and mechanical relays in a computer. One of the fastest machines of its day with 320 K of memory (!), it also was connected to Xerox’s first computer printer, had one of the first display screens (9 inches in width), and, fatefully, a light-pen (already in use by the first computer-based radar systems).

While Sketchpad was a 2-D program, later versions by Sutherland had 3-D wireframes, the forerunner of modern CAD (Computer Aided Design) systems. Sketchpad 3 even included the division of the screen into 4 views, now standard in all 3D software (above, side, front, and in perspective). Sutherland utilized this kind of software in another innovation.

Ivan Sutherland was already exploring virtual reality in the 1960s.

In 1966, now a professor at Harvard, he developed a head-mounted display inside a helmet to project an immersive three-dimensional graphics environment. The movements of the wearer’s eyes or bodies were tracked and the perspective of the image would make corresponding changes—in short, it was the first virtual reality display. It generated a 3D effect by projecting a separate wireframe image for each eye. Called the “Sword of Damocles” because of its great weight, it had to be suspended from wires on the ceiling to avoid crushing the viewer.

University of Utah

In 1968, Sutherland left Harvard to join the newly founded University of Utah’s Computer Science department, whose focus was on the new field of computer graphics.

As an influential professor, Sutherland became not only the father of computer graphics but the grandfather of the computer age. The list of Sutherland’s students at the University of Utah is a Who’s Who of computer pioneers.

- Nolan Bushnell and Pong, c. 1972

- Ed Catmull in Pixar’s render farm, c. 1974.

- John Warnock and the first Adobe Illustrator

Nolan Kay Bushnell would go on to start Atari and give birth to the computer game industry. Ed Catmull, led the 3D animated film revolution as one of the founders of Pixar. John Warnock invented Postscript and the PDF format, as well as launching the software giant Adobe Systems. Other former students helped create Netscape, Silicon Graphics, and WordPerfect.

Talented graduate students at the University of Utah also invented most of today’s methods for realistically shading three-dimensional objects. Before he started Pixar, Ed Catmull’s Ph.D. dissertation established the concept of texture mapping, which wraps a photo-realistic image of a texture around a wireframe form. In 1971, Henri Gouraud conceived Gouraud shading, where by blurring the facets of a polygon, an object can appear to be smoothly shaded. In 1974, Phong Bui-Toung, created Phong shading, creating realistic highlights on shaded objects. In 1976, Martin Newell and Jim Blinn developed reflection mapping, where objects are shaded with reflections from their environment. Blinn also developed the technique of bump mapping, allowing shading of irregular surfaces. More than forty years later, these methods still dominate the rendering of 3-D images in animations and computer games.

James Blinn, Voyager 1 approaching Saturn, 1980

After graduation, Blinn was hired by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratories to create computer graphics simulations of the first Voyager missions to explore Saturn and Jupiter. When broadcast on television after take-off, they became the first looks the public had into the new world of 3-D animation. Surprisingly cinematic, many newscasters assumed Blinn’s animations were actual footage of the spacecraft’s voyage.

Xerox PARC

Remarkably, Sutherland created Sketchpad, the first interactive drawing software, not for art’s sake. Instead, his goal was to use graphics as the first way to communicate directly with a computer. This goal, and the design of his program, are why many also consider him the grandfather of the Graphical User Interface or GUI, the concept behind folders and icons on your computer’s desktop. However, its real father was another student of his, Alan Kay.

Perhaps less known than other Sutherland protégées, Kay may be the most influential. As a student, he experimented with Sutherland’s Sketchpad program. After graduation, he became a researcher at Xerox Corporation’s Palo Alto Research Center (Xerox PARC).

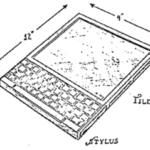

Alan Kay concept drawing of a laptop – “Dynabook”, 1972

Alan Kay is credited with the slogan, “The easiest way to predict the future is to invent it.” At PARC, he changed the idea of what computing could be. Rather than a world of huge computers run by experts, he imagined computers as small as books that were so easy to use that his mother could take one shopping. They would be true multimedia computers, integrating images, animation, sound, and text. Kay was part of a team that developed a computer that included many of these ideas. It was called “Alto” – and it revolutionized computing.

Children using the Alto, c. 1970.

Until the Alto, computers had always been huge, expensive machines housed in a dedicated air conditioned facility. Alto, however, was a small computer that sat on a desk and was designed for one user—in essence, the first personal computer. It had its own keyboard and used a mouse for input. Its monitor was the size of a typical page. It even had removable disks for storage.

The graphical interface Alan Kay designed for the Alto computer at Xerox PARC

Equally revolutionary was the Alto’s use of Kay’s concept of a graphically designed system of interacting with the computer—the first of what would become known as a Graphical User Interface (GUI). Kay’s approach would be quite familiar to today’s computer users. Each element on the screen was a picture, or icon. The icons were designed with an office metaphor; so information was put into files, files into folders. Clicking the mouse on an icon started a program. The interface even allowed for multiple windows and pop-up menus.

Because on an Alto every pixel on the screen was used to picture forms rather than text or shapes composed of vectors, what one saw onscreen was quite close to what was printed. This new bitmap approach became known as “what you see is what you get” or WYSIWYG (pronounced “wizzy-wig”).

Xerox never put the Alto into production, but its ideas would come to life after a young computer geek with a startup company was given a tour of their labs (over the objections of Xerox engineers) and saw Kay’s prototype. His name was Steve Jobs. What he saw inspired the Apple Macintosh and led to the personal computing revolution. Kay never held this “theft” against Jobs and would later advise him on the early versions of the iPhone and iPad, as well as help him with his acquisition of Pixar.

While Sutherland’s students were busy developing or inspiring the building blocks of the computer age, Father Ivan continued his own research in computer graphics at a company he co-founded with Dave Evans, a colleague from the University of Utah. Their company’s hardware and software systems were among the first graphics systems made available to the public. Their research also laid the foundation for all simulators used to train pilots and astronauts, as well as projection systems for planetariums.

Scene from an Evans & Sutherland Simulation

In the 1970s, Sutherland joined the faculty at California Institute of Technology and shifted his research and teaching away from graphics to integrated circuit design – helping to create the foundation for the modern computer chip industry and Silicon Valley. In the 1980s, he formed a new company which was later sold to and became an important part of Sun Microsystems.

In 2009, Ivan Sutherland married Marly Roncken, and together they established the Asynchronous Research Center at Portland State University to develop self-timed asynchronous computers (all computers are slowed down because their central processor’s clocks must accommodate their slowest components).

Ivan Sutherland, 2012

Now in his 80s, after a career that gave birth to computer graphics, virtual reality, flight simulators, computer controlled robots and inspired the modern chip industry and personal computing, Father Ivan continues to explore new technologies and have fun as a self-described, “Engineer, Entrepreneur, Capitalist, Professor.”