As the sun set in Paris, on January 8, 1927, Pablo Picasso was walking past a fashionable department store when his eyes fell upon a young shopper. Immediately infatuated, the artist (then unhappily married and in his mid-forties) took Marie-Thérèse Walter by the arm and said, “I’m Picasso! You and I are going to do great things together!” She was confused by the man and unaware of who he might be. Picasso introduced himself by dragging her into a bookshop and showing her a book filled with reproductions of his paintings. Thus began a passionate affair and an enormously productive period for Picasso.

As the sun set in Paris, on January 8, 1927, Pablo Picasso was walking past a fashionable department store when his eyes fell upon a young shopper. Immediately infatuated, the artist (then unhappily married and in his mid-forties) took Marie-Thérèse Walter by the arm and said, “I’m Picasso! You and I are going to do great things together!” She was confused by the man and unaware of who he might be. Picasso introduced himself by dragging her into a bookshop and showing her a book filled with reproductions of his paintings. Thus began a passionate affair and an enormously productive period for Picasso.

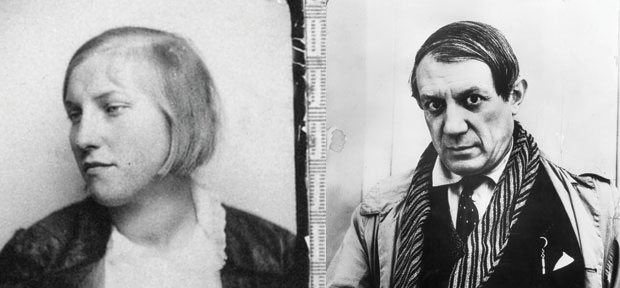

Picasso, Marie-Thérèse, 1928

Seventeen at the time, Marie-Thérèse lived with her family and, like other teenagers – past and present, told them she was going to a girlfriend’s house while actually leaving for a rendezvous. But in her case the trysts were with the world’s most famous artist. By spring, they were meeting every day, so Marie-Thérèse invented an imaginary job to explain her absences to her parents.

Marie-Thérèse Walter, 1936, photograph by Pablo Picasso

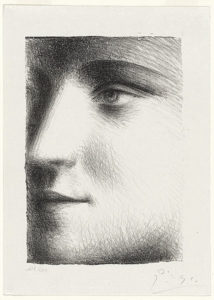

Picasso once said that “Painting is just another way of keeping a diary” and one way to understand his work, as abstract as it may appear, is to follow its stages through the women he loved. Picasso’s paintings initially referred to Marie-Thérèse in a kind of visual code. In the first pictures, she is depicted as fruit in a bowl or a guitar. This change in his style is a clue to her identity. His new lover was not a thin dancer like his wife, but a sturdy athletic young woman, with a Grecian nose, large breasts and strong legs. The previously hard edged, angular shapes of his Cubism make way for rounded, sensual lines. Soon, he abandoned this subterfuge and portrayed Marie-Thérèse directly – in sketchbooks full of drawings, etchings, sculptures and paintings. Their passion made them reckless and daring. Even while vacationing with his wife and child on the French coast, Picasso found a small hotel for Marie-Thérèse nearby. They met secretly in a cabana while his wife played with his son on the beach.

- Picasso, Sketch, 1928

- Picasso, Bather with Beach Ball

- Picasso, Woman with Yellow Hair, 1931

- Picasso, Still Life with Tulips, 1932

- Picasso, Sculpture of a Head, 1932

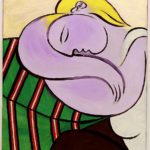

- Picasso, The Dream, 1932

- Picasso, Nude on a Black Armchair, 1932

- Picasso, Marie-Thérèse, 1937

In the year before they met, Picasso had experienced a lull in his creativity that was very unusual and painful for him. Now, there was a flood of pictures. It was, as he told Marie-Thérèse, that he never tired of looking at her. He particularly loved to paint her when she was asleep.

Picasso, The Dreamer, 1932

The Dreamer from 1932 is a good example of Picasso’s new approach to painting. Cubism was no longer a drab, strict, analytical study of forms but a doorway to freedom and creativity. The artist explores his passionate feelings with curving, voluptuous forms and colorful, luscious, thick paint. The sleeping Marie-Thérèse appears as a lovely, sexual being in harmony with nature.

In the summer of 1936, Picasso wrote her,

I love you more than the taste of your mouth,

more than your look,

more than your hands,

more than your whole body,

more and more and more and more than all my love for you will ever be able to love

and I sign

Picasso.

Picasso, Girl Before Mirror, 1932

In this period before World War II, Marie-Thérèse appeared in many guises: model, muse to the gods, and even a Madonna in Girl Before Mirror. In 1935, their daughter Maya was born and she, too, became a favorite subject.

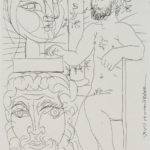

- Model and Rembrandt

- Faun Revealing a Woman

- Blind Minotaur Guided Through a Starry Night by Marie-Thérèse

From 1930 to 1937, their love affair inspired one of the high points in Modern printmaking — a set of etchings that have come to be known as the “Vollard Suite.” They were named for the French art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, who commissioned them and gave Picasso his first Paris exhibition. Most of the one hundred etchings are set in a mythical sculptor’s studio along the Mediterranean. Filled with classical themes of love and passion, one subject is dominant — an artist and his adoring model living in paradise. At this time, Picasso and Marie-Thérèse were living in their new home and studio, the Château de Boisgeloup outside Paris.

Dora Maar in Picasso’s studio in Paris, 1946

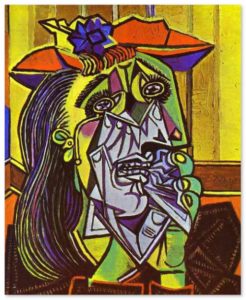

But Paradise was about to be lost. Sometime around 1936, Picasso met Dora Maar, a well-known photographer and artist, and she began to compete with Marie-Thérèse for his affections. Maar would become his next muse, portrayed in many pictures of the late 1930s and early 1940s, as well as serving as the model for the grieving mother in Guernica. He later said that for him, [Dora] was always the weeping woman.

Picasso, Weeping Woman, 1937

After their affair ended, Picasso continued to support Marie-Thérèse and their daughter. He provided an apartment in Paris and a home in the South of France. Even as Picasso moved on to other mistresses over the next forty years, Marie-Thérèse remained devoted to the memory of their love and always hoped he would return to her. They continued to write each other. Picasso had once told her that she had saved his life and his art of the 1930’s documents their great passion. According to his friend and biographer, John Richardson, she “was the greatest love of his life; he absolutely adored her…He had her in mind always, all the time; everything relates to her.”

Sadly, life in a world without Picasso was too much for Marie-Thérèse. Four years after the artist’s death in 1973 and fifty years after they first met, she hung herself in the garage of her home in the South of France.

[Adapted from Lewis and Lewis, The Power of Art, third edition.]

Hi,

The name of Marie Thèrèse Walter appeared to me in article in the VEJA, a Brazilian magazine, which treated about the problems of sleep because the pandemia. A reproduction of a Picasso’s painting of Marie Thèrèse ilustrated the article.

I looked like about this person at web and I found your text.

I’d like to say you your article is very good, and exposed the deep love between the artist and the beautiful French woman.

I’d like to thank you.