While at the Cleveland Art Museum earlier this month, my attention was caught by an impressive plaster head by Rodin. It was immediately familiar as a large scale version of one of the heads from his famous The Burghers of Calais, but I thought it even more moving in its own right. The marks of Rodin’s fingers as he created such a sorrowful expression were amplified by pencil marks and the traces of colored washes — I never knew Rodin did such things. But I was surprised a second time when I read the label and it said “Gift of Loïe Fuller.”

I was already aware that Loïe Fuller was an extraordinary woman. Could she be even more extraordinary than I knew?

Marie Louise Fuller was born in 1862 on a farm outside of Chicago. As a young girl, she was inspired to be an actress by Sarah Bernhardt. She found her truer calling while acting in a play, when she twirled her long white skirt in a way that suggested a rising butterfly. The audience loved it and soon she was performing across the country as a dancer in vaudeville, burlesque, and even Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Known best for her free-spirited Serpentine dance, today she is considered one of the founders of Modern Dance despite never having taken any lessons. But it wasn’t until she was 30 and crossed the Atlantic that she became one of the most famous dancers in the world.

Marie Louise Fuller was born in 1862 on a farm outside of Chicago. As a young girl, she was inspired to be an actress by Sarah Bernhardt. She found her truer calling while acting in a play, when she twirled her long white skirt in a way that suggested a rising butterfly. The audience loved it and soon she was performing across the country as a dancer in vaudeville, burlesque, and even Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Known best for her free-spirited Serpentine dance, today she is considered one of the founders of Modern Dance despite never having taken any lessons. But it wasn’t until she was 30 and crossed the Atlantic that she became one of the most famous dancers in the world.

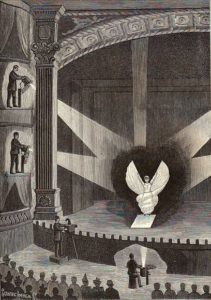

As Loïe Fuller, she became the toast of Paris when she opened her show at the Folies-Bergère in 1892. At the center of an empty dark stage, Fuller entered in a white silk costume of her own design and then flung the material out in ever-changing huge abstract forms. Unbeknownst to the audience, inside hundreds of yards of fabric, she had sewn in bamboo sticks to push out the shapes. Colored lights, manipulated with mirrors from the sides of the stage, illuminated the billowing forms. Audiences were mesmerized by the magical metamorphosis taking place before their eyes.

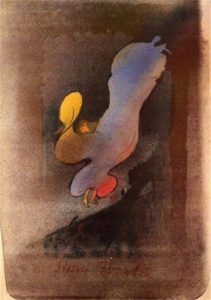

- Toulouse-Lautrec -1893. Color brush and spatter lithograph, touched with gold or silver powder

- Alphonse Mucha – 1898

- Jules Chéret – 1893

At the Folies-Bergère and other venues like the Paris Opera, Fuller earned a place in Art History, too, as the inspiration for many artists, designers, and writers at the turn of the century. Called by her fans “La Loïe,” she was popular with photographers, filmed by the Lumiere Brothers and Thomas Edison, and the subject of great prints by Toulouse-Lautrec, Alphonse Mucha, and Jules Chéret. At the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris (which introduced the world to the Eiffel Tower), Fuller had her own theater designed in the style of Art Nouveau, a movement that recognized a kindred spirit in her dances’ natural curving sculptural forms. The French poet Stéphane Mallarmé described her as “an artist of intoxication” and compared her dancing to a “theatrical form of poetry par excellence.”

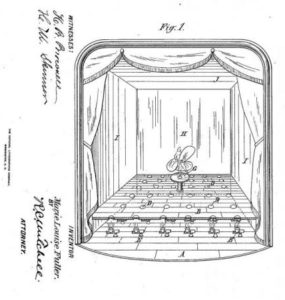

- Loïe Fuller: under stage lighting patent, 1894

- Scientific American June 20, 1896

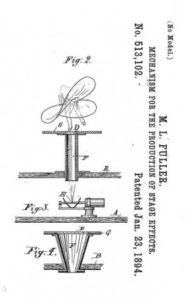

- Loïe Fuller: patent, 1894

Fuller constantly experimented with new effects, for example, magic lantern image projections on her costumes. She patented many of her innovative lighting techniques, such as painted colored gels for lights. She also consulted with Thomas Edison (whose incandescent lamps were essential to her success) and Marie and Pierre Curie about new methods, like phosphorescent clothing dyes with radium. Not all her experiments were wise – once an explosion burned off her hair.

- B.J.Falk, Loïe Fuller, 1892

- Samuel Joshua Beckett, Loïe Fuller, c. 1898

Her physique was not one normally associated with dancers. Fuller was not particularly beautiful; her body was short and stocky. She was, in person, a bit clumsy, quite shy and often giggled nervously. But once on stage her choreography allowed her to disappear into her costumes – it was the movement of those sculptural forms that sent audiences into rapture — not her actual body’s movements.

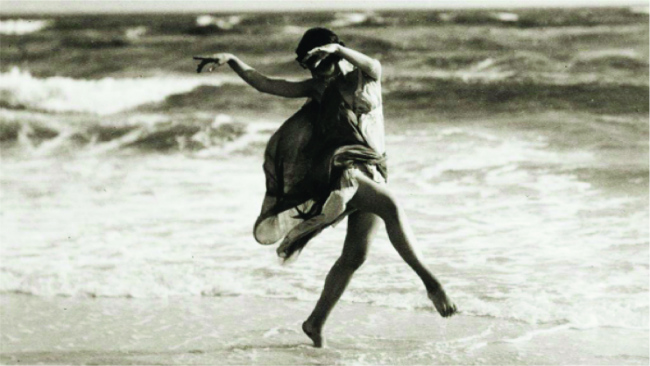

Isadora Duncan

In 1901, she added another credit to an already historic resume when she discovered a young woman from San Francisco — Isadora Duncan — and brought her into her dance troupe. Her lovely protégée had a body that was naturally lean and expressive. Audiences immediately fell in love with her (as did Fuller). Duncan, unlike Fuller, had started studying ballet at six and would ultimately pioneer what she described as ‘natural dance’ inspired by the movements of the sea. Loïe’s fascination with the barefoot dancing Duncan was recently the subject of the French film “La Danseuse.” After leading Fuller along, Isadora would soon abandon the older dancer and become one of the great historic figures in dance. As Duncan’s career begin to rise, Fuller’s began a slow decline.

Rodin, Head of Pierre de Wissant, 1886. 33″ tall, Plaster.

Her name on the Rodin sculpture’s label at the Cleveland Art Museum opens the door to the next chapter in Fuller’s life. By 1917, already 55, she knew that her wild and frenetic dancing career was coming to an end. Her friendships with the artists of Paris like Rodin led her to act informally as their agent. When she came to Cleveland in 1917 to raise money for the Red Cross, she also gave a lecture at the Art Museum on Rodin. She then donated the wonderful large plaster head by him that I so admired. She also introduced an American collector, Alma de Bretteville Spreckels (an artist’s model who married a sugar baron — and may have been the first to call someone a “sugar daddy”), to Rodin himself, which would ultimately result in what Fuller called “the greatest collection of perfect Rodins in the world.” Seventy of these sculptures were later donated to San Francisco’s Legion of Honor. Loïe would live the remainder of her life with her business partner, Gabrielle Bloch, who managed Fuller’s traveling dance troupe of “Muses.”

The funeral of Loïe Fuller in Paris.

Loïe Fuller was 65 when she died in 1928 . Her epitaph may be best expressed by her life long friend, Auguste Rodin, who once wrote:

All the cities she has visited, and Paris, owe to her the purest emotions, and Loïe Fuller has reawakened sublime antiquity. Her talent now will always be imitated, and her creations will live forever, for she has sown the seeds, and her effects, lights and ‘mise en scène’ are all things which will be studied.

Fittingly, her ashes are buried in Paris’s Père Lachaise cemetery along with many other great historic figures like the writers Oscar Wilde, Proust, and Balzac, the artists David, Ingres, Géricault, and Delacroix, the composers Bizet, Rossini, and Chopin, her early inspiration, the actress Sarah Bernhardt, and ironically, another dancer — Isadora Duncan.