A strange, life-size doll is at the center of one of the Modern era’s most bizarre episodes. Its inspiration was the sudden end of an intense love affair between the Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka and the fascinating Alma Mahler.

A strange, life-size doll is at the center of one of the Modern era’s most bizarre episodes. Its inspiration was the sudden end of an intense love affair between the Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka and the fascinating Alma Mahler.

Born in 1879, Alma Maria Schindler grew up surrounded by the best of Viennese society. Her father was a noted painter; Crown Prince Rudolf was one of his patrons. While she would become a composer and a writer, it is her love affairs with some of the most important artists, architects, and composers of the 20th century that have kept her celebrity alive since her death in 1964.

Alma Schindler, 1898

As a teenager, she first began composing music. Also interested in painting lessons, Alma was introduced by a friend to Gustav Klimt, the leader of the Viennese Succession. The painter fell in love with her and gave Alma (already considered ‘the loveliest girl in Vienna’) her first kiss at 17 on a trip to Italy. While it is unclear whether the kiss led to much more, the two remained friends until his death in 1917. Alma wrote of him

‘Gustav Klimt entered my life as my first great love, but I was an innocent child, totally absorbed in my music and far removed from life in the real world. The more I suffered from this love, the more I sank into my own music, and so my unhappiness became a source of my greatest bliss.’

Klimt appears to have had a premonition of Alma’s future when he wrote

‘She has everything a discerning man could possibly ask for from a woman, in ample measure; I believe wherever she goes and casts an eye into the masculine world, she is the sovereign lady, the ruler.’

She next fell in love with her music teacher, the Jewish composer Alexander Zemlinsky. However, she broke off that affair to marry a more famous conductor and composer, Gustav Mahler. Alma was already pregnant with their first child, and another soon followed. Nearly twenty years older than Alma, Gustav Mahler was then the conductor of the Viennese Court Opera, where he introduced the city to Wagner’s Ring Cycle. Mahler had no interest in Alma’s composing and told her

“The role of composer, the worker’s role, falls to me, yours is that of a loving companion and understanding partner …”

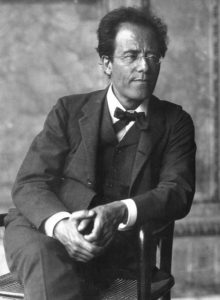

Gustav Mahler

Alma reluctantly gave up the piano and composing and devoted herself to their growing family and supporting her husband’s career – a very painful decision. Writing music had been her dream, something she “lived for.” ‘I should like to do a great deed, like to compose a really great opera, something no woman has ever done before.’ No wonder when thinking of her sacrifice, she wrote in her diary: “How hard it is to be so mercilessly deprived of … things closest to one’s heart.”

The Mahler family experienced a double crisis in the summer of 1907. Their five-year old daughter Maria died after a sudden illness, and Mahler himself was diagnosed with a serious heart condition. Alma became deeply depressed and went to a spa to recover. There she began an affair with a young architect — Walter Gropius — who would go on to be the founding director of the influential Bauhaus, arguably the most important art school of the 20th century.

Gustav found out about the affair (Gropius “accidentally” addressed a love letter to the Mahler home) and even consulted the eminent psychotherapist Sigmund Freud on how to best save his marriage to Alma. It is speculated that Freud encouraged Mahler to let Alma return to her composing. Given the chance, she began writing songs again, some of which were published with her husband’s help. Eventually, she did break off the affair at Mahler’s urging. But this period was cut short when Mahler’s heart condition left him susceptible to an infection, which eventually led to his death.

Oskar Kokoschka

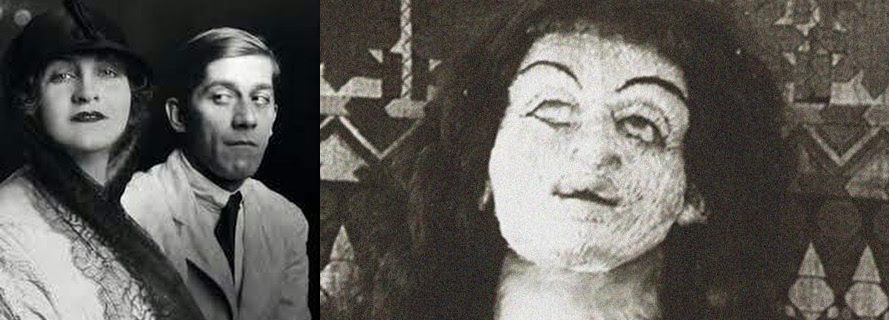

Double Portrait of Kokoschka and Alma Mahler, 1912-1923

After Mahler’s death, she began an affair with an even younger man – the painter Oskar Kokoschka. She was the love of his life. They met at a party in 1912 where Alma was playing the piano. According to her, Kokoschka suddenly “pulled me into his arms…a strange, almost shocking and violent hug.” Later that day, he proposed marriage.

While she refused his proposal, both were swept away by their passion. Alma also reveled in his devotion to her and, years later, remembered their time together like this:

‘Never before had I savored such convulsion, such hell, such paradise. I experienced his rise… I took care of him, as far as possible. He painted me, me, me!’

Oskar Kokoschka

The Bride and the Wind, 1914

Their passionate relationship inspired Kokoschka’s most famous painting, The Bride of the Wind. Its expressionist brushstrokes visualize the intensity and turbulence of their affair, as the wind-blown lovers are carried away into the sky, far from the world below. It is almost an illustration of a description Alma wrote of one of their days together:

“On a stormy tormented day when he passionately, but entirely selfishly loved me, the world melted away suddenly, and I have since been convinced of an outer-worldly existence.”.

These intense feelings did not last – at least for Alma. Kokoschka was devastated when the pregnant Mahler aborted their child. When World War I broke out, he volunteered for the Austrian army and was severely injured by a bayonet to the chest in Russia. Doctors in the military hospital decided he was mentally unstable and sent him home for nursing. Once home, Kokoschka was horrified to discover that while he was away Alma had married her former lover, Walter Gropius.

Walter Gropius and Alma Mahler with daughter Manon, 1918

Kokoschka begged her to return to him.

‘I must have you for my wife or my genius will self-destruct. You must resuscitate my soul, each night, like an elixir’

Oskar Kokoschka

Knight Errant, 1915

Alma told Oskar that she had to break off their relationship because it frightened her and was too overwhelming. Since the devastated Kokoschka could not imagine living without her, his obsessive desire inspired him to conceive of a bizarre substitute. He commissioned a doll maker, Hermine Moos, to make him a life-size Alma doll.

If you are able to carry out this task as I would wish, to deceive me with such magic that when I see it and touch it imagine that I have the woman of my dreams in front of me

Peter Paul Rubens

Helene Fourment in a Fur Coat, 1630s

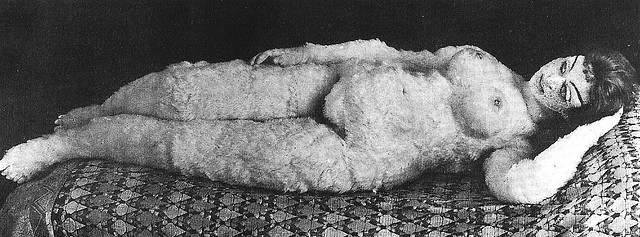

He told Moos to try to make her look like the voluptuous second wife as seen in the portraits of Pieter Paul Rubens, whom the Baroque painter immortalized in a famous nude portrait. Yet, unlike the loving image created by the Flemish painter, there is a weird literalness in Kokoschka’s commission.

Yesterday I sent a life-size drawing of my beloved and I ask you to copy this most carefully and to transform it into reality. Pay special attention to the dimensions of the head and neck, to the ribcage, the rump and the limbs. And take to heart the contours of body, e.g., the line of the neck to the back, the curve of the belly. Please permit my sense of touch to take pleasure in those places where layers of fat or muscle suddenly give way to a sinewy covering of skin. For the first layer (inside) please use fine, curly horsehair; you must buy an old sofa or something similar; have the horsehair disinfected. Then, over that, a layer of pouches stuffed with down, cottonwool for the seat and breasts. The point of all this for me is an experience which I must be able to embrace!

Oskar Kokoschka

Letter to Hermine Moos

While Moos was at work, Kokoschka kept writing her. In one letter, he asks, “Can the mouth be opened? Are there teeth and a tongue inside? I hope.” After six months, the doll was completed and arrived at his home. Kokoschka tore open its crate,

“In a state of feverish anticipation, like Orpheus calling Eurydice back from the Underworld, I freed the effigy of Alma Mahler from its packing. As I lifted it into the light of day, the image of her I had preserved in my memory stirred into life. “

But all was not as he imagined. Despite his creepy, explicit directions for the doll’s skin, the doll-maker had covered his Alma doll in feathers. He complained to Moos that he couldn’t even dress her and that her skin was more like a “polar bear rug.” Still, he did not give up on his morbid fantasy. He posed the doll in various positions in his studio, dressed her in elaborate costumes, and made many drawings, paintings, and photographs of her — clothed and unclothed. Reportedly, he rode in carriages with the faux-Alma and even brought her as his guest to an opera.

But all was not as he imagined. Despite his creepy, explicit directions for the doll’s skin, the doll-maker had covered his Alma doll in feathers. He complained to Moos that he couldn’t even dress her and that her skin was more like a “polar bear rug.” Still, he did not give up on his morbid fantasy. He posed the doll in various positions in his studio, dressed her in elaborate costumes, and made many drawings, paintings, and photographs of her — clothed and unclothed. Reportedly, he rode in carriages with the faux-Alma and even brought her as his guest to an opera.

Oskar Kokoschka

Self-Portrait with Doll, 1912

In the end, despite his best attempts to recreate his lost love (or reduce his human mistress to a mannequin), he only experienced frustration with his doll because of its “inescapable thingness.” As a finale to his mock affair, he threw a champagne party with a chamber orchestra playing for her. For one last time, he dressed the doll in fabulous clothing. At the party’s end, the drunken Kokoschka dragged “Alma” to his garden, cut her head off, and broke a bottle of red wine on her. Unable to possess the real Alma, he murdered her replica.

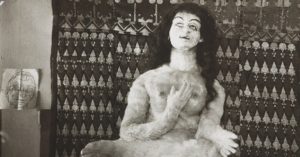

Oskar Kokoschka’s Alma doll, 1919.

Early the next morning, police woke Kokoschka to investigate a report of a woman “drenched in blood” seen in his garden. Hung over, he wrapped a robe around himself, went downstairs and showed the police a lifeless, decapitated doll soaked in wine.

Kokoschka would go on to a successful international career as a painter. In the 1940s, he married a woman who was 30 years younger. He also found himself on the list of Adolf Hitler’s “Degenerate Artists.” His wife, a lawyer, organized their escape to first Czechoslovakia and then Scotland. After the war ended, Olda and Oskar settled in Switzerland, where he would die in 1980 at the age of 93.

As for the real Alma Mahler, she would later divorce Walter Gropius and marry the Czech poet and writer Franz Werfel, the author of The Song of Bernadette. Together, they would immigrate to the United States and settle in Los Angeles. There, she became a grand hostess, entertaining many of the talented refugees who fled Europe during World War II. Thomas Mann and Igor Stravinsky were among the many people who attended their parties.

The director Max Reinhardt with Franz Werfel and Alma Mahler in Hollywood

While married to Werfel, she continued having affairs, including one with a young priest. After Werfel’s death, Alma Mahler moved to New York City, where, before her death at age 85, she entertained a new generation of writers, artists, and composers, such as Leonard Bernstein (a lover of Gustav Mahler’s music).

What was the secret to Alma’s allure? All who knew her agreed that she was intelligent, an excellent conversationalist, and beautiful. One theory of her charm is that because she was deaf in one ear, she would lean closely into whoever was talking to her, creating an immediate intimacy.

Alma has been the target of much criticism over the years. Cast as a femme fatale (one biography is titled Malevolent Muse), she was said to be “cold” despite her multiple love affairs (and the evidence of her own words, above, describing her overwhelming passion for Kokoschka). However, a recent study from 2019 argues instead that Alma Schindler Mahler Gropius Werfel was A Passionate Spirit, one who was forced to deal with the restrictions placed upon women of her period and class by becoming the mistress, or wife, of a series of powerful men. According to the blurb posted on Amazon,

“Passionate Spirit restores vibrant humanity to a woman time turned into a caricature, providing an important correction to a history where systemic sexism has long erased women of talent.”

Whatever the reason, her lovers and friends are nearly a who’s who of 20th century modernism. While only 14 of her own songs have survived, she inspired many poems, paintings and music. As well as a strange, feather-covered doll.

Hermine Moos with her Alma Doll

Congratulations, article, information and photographs are excellent. Thank you.

Pingback: 5 saggi d’arte + 1 – il libro geniale

I loved the story you wrote. I’m fascinated … Now I want to learn more about these artists and increased my interest in dolls. I’ve always loved them but look at them in a totally different way.