After World War II, the center of the art universe shifted and New York City replaced Paris as the home of the avant-garde. In Manhattan’s downtown bars and studios, passions ran high. Arguments about art and ideas often turned into celebrated drunken brawls. Amidst the turbulent turf wars, one art critic reigned supreme – Clement Greenberg. His discovery of Jackson Pollock led to the rise of Abstract Expressionism as the dominant art form in the post-war art world. His opinions were followed intensely, even feared, by artists, dealers, and collectors.

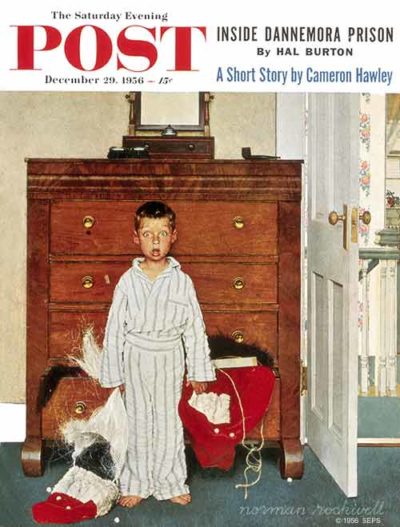

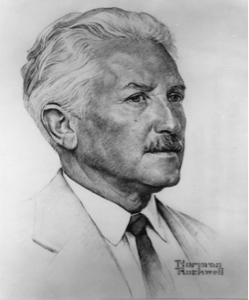

Yet, despite the New York School’s position as the foremost movement in Modern Art, if you asked most Americans in the 1950s to name their favorite artist, they would probably have said Norman Rockwell, the beloved illustrator of covers for the Saturday Evening Post. For decades, the Post had been the most popular magazine of its time. Self-proclaimed as “America’s Magazine,” its covers depicted an ideal small-town America, not unlike the New England towns where Rockwell spent most of his adult life. In fact, his models were often his neighbors. His covers were regularly turned into posters and found their way onto the walls of homes across the country.

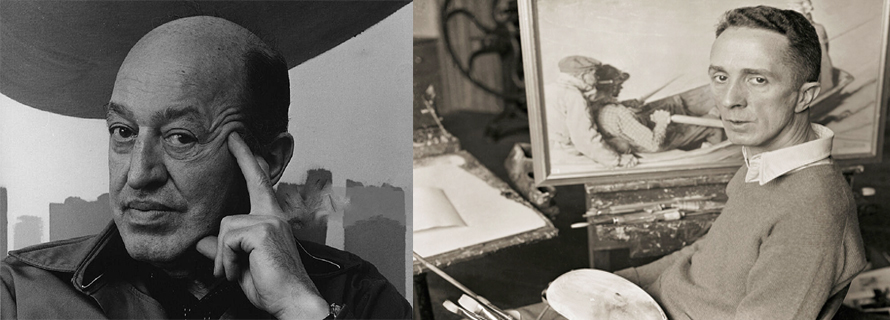

This frustrated Clement Greenberg, who was justifiably proud of the emergence of New York as the global center of art. In his best-known essay, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” he struggled to understand how such a strange state of affairs was possible and why the citizens of his country were not embracing their great cultural victory. At the end of its very first sentence, he almost calls out Rockwell by name:

“One and the same civilization produces simultaneously two such different things as a poem by T. S. Eliot and a Tin Pan Alley song, or a painting by Braque and a Saturday Evening Post cover.”

For Greenberg, popular art or kitsch like Rockwell’s was a sign of the “decay” of society, made from “debased” materials and not “genuine culture.” “Kitsch is the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times. Kitsch pretends to demand nothing of its customers except their money – not even their time.”

While one might see the clash of values between Greenberg and Rockwell as just another example of the time-worn cultural battle between city dwellers and country folk, it wasn’t. Both men were actually native New Yorkers. Greenberg was the child of Jewish immigrants who was born and went to school in the Bronx.

Rockwell not only grew up in the city (he was born in a boarding house on 103rd Street, near Amsterdam Avenue), but trained at some of its finest art schools – the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League. His first studio was in Hell’s Kitchen and his second just under the Brooklyn Bridge. Even though he would ultimately spend most of his adult life in New England and be identified with it, he never lost his Upper West Side accent.

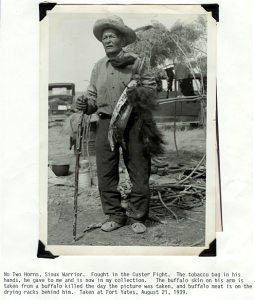

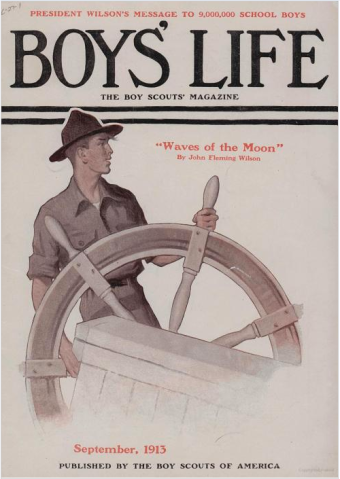

While still in school, Rockwell’s illustration career took off. By the time he was 19, he was the art editor of Boy’s Life, the official publication of the Boy Scouts of America. The next year, he created his first cover for the Saturday Evening Post.

While Rockwell was, of course, proud of his success, he also was well aware of the criticisms of his subject matter by critics and fellow artists. He would defend himself in statements like, “I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed.”

But deep down, he also wished his work would be accepted by art critics and ultimately judged as worthy of the great museums. During a visit to Rembrandt’s house in Amsterdam, he reportedly yelled, “Rembrandt? It’s me, Norman.… What do you think?”

In reality, like many artists, Rockwell was secretly plagued by doubts and wondered if his work was really any good. During the 1950s, Rockwell was treated by Erik Erikson, the famous psychiatrist who coined the term “identity crisis.” Rockwell had recently moved his family from Vermont to the Berkshires, so his wife could get treatment at the Stockbridge Massachusetts clinic where Erikson worked. Rockwell and the psychoanalyst became good friends. Erikson, who as a young man had tried to be an artist, would even give Rockwell suggestions on ways to develop his paintings.

While America embraced Rockwell, the art world did not. As for Clement Greenberg, he showed no sign of budging in his assessment of Rockwell. His dismissal of Rockwell at times even approached cruelty: “you have to put Rockwell down, down below the rank of minor artist. He chose not to be serious.”

The Secret Visit

Greenberg’s callous statement makes an event from 1951 appear inexplicable. On August 16th, Greenberg, along with the painter Helen Frankenthaler, paid a secret visit to Rockwell’s personal studio. His appointment calendar for the day notes: “Norman Rockwell’s at 5.”

What could possibly have motivated the titan of avant-garde theory to ask for this meeting? And why would Rockwell, who surely knew of Greenberg’s animosity to his art, agree to it?

The key can be found in the dream of a first-generation American kid from the Bronx. What no one familiar with his essays and ideas would ever guess is that as a young man “Clem” idolized Norman Rockwell.

Like many children of upwardly striving immigrants, Clement Greenberg was expected to work with his father once he finished school. But he rebelled because he had other ideas. Greenberg was determined to be an artist – an artist like Norman Rockwell. Perhaps as a first-generation American, he saw those iconic images as a path to legitimacy.

He drew insistently and painted many pictures. In time, however, Greenberg realized that he could never be a successful artist like Rockwell and abandoned his dream for the life of an art critic.

From Frankenthaler’s account, we can tell that the visit in the summer of 1951 was not what one would expect – a clash of titans from opposite sides of the American art world. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth.

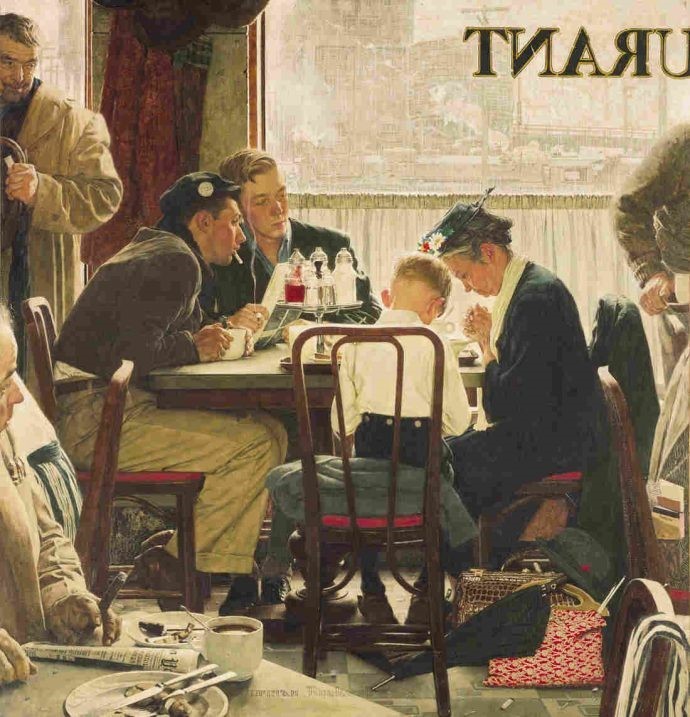

They were welcomed by Rockwell into his studio. On his easel, Greenberg and Frankenthaler saw what would become one of Rockwell’s most famous paintings, Saying Grace, in progress. Rockwell explained that it was going to be the cover for the upcoming Thanksgiving issue of the Saturday Evening Post.

At this point, it only had its underpainting, all in grays, as is typical in academic paintings. The painting showed a grandma and grandson praying in a diner while two teenagers seem perplexed by their behavior.

Saying Grace was as far from an avant-garde painting as could be imagined. Yet, the art critic and young artist were taken with it. They told Rockwell it was wonderful and begged him to make no further changes.

During the visit, Greenberg revealed to Rockwell that he had loved his work as a young man. We can only assume that the older artist was truly touched by this. According to Frankenthaler, Rockwell’s modest and kind response to Greenberg was, “I hope your taste has grown.”

Norman Rockwell: Abstract Expressionist

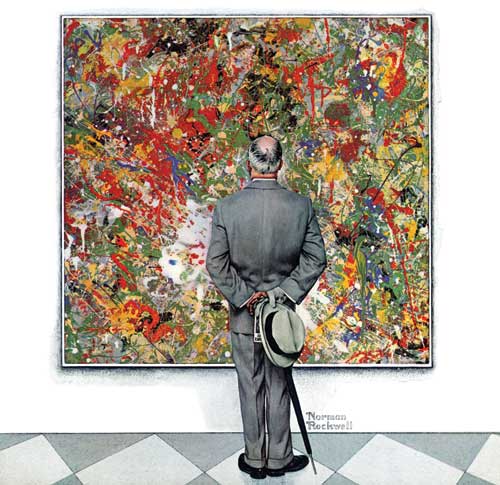

Because of a painting from ten years later, we can guess that Greenberg’s visit made a lasting impression on Rockwell. In Connoisseur from 1961, for once the illustrator decided to follow the dictums of Clement Greenberg and threw himself into fully experiencing action painting.

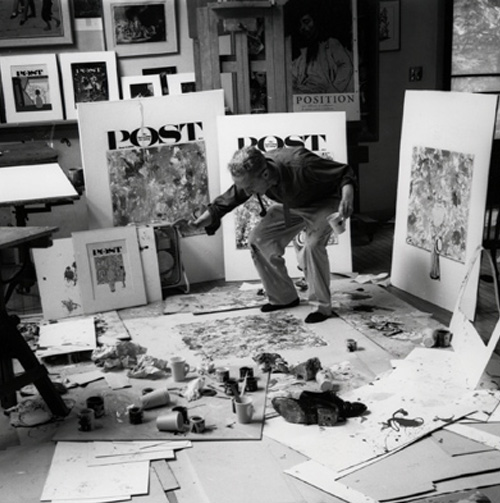

Rockwell built Connoisseur in three steps. The most remarkable was the first. After studying articles in art magazines, he painted a convincing abstract expressionist canvas. Imitating Jackson Pollock‘s working methods, Rockwell spread the canvas on the floor and moved around it as he flung paint.

Then he switched back to his normal approach and made a painting of just the observer. Finally, he combining the two as a collage and painted a final version based on it that ultimately became the cover for the Saturday Evening Post.

Rockwell liked the first abstract canvas enough to divide it into at least two other paintings that he submitted to exhibitions, although he kept his identity secret by signing them with an Italian name. At the Cooperstown Art Association in New York, one part of Connoisseur took first prize for painting. Another section won Honorable Mention at the Berkshire Museum.

The Connoisseur cover was not an ironic effort by Rockwell to mock Abstract Expressionism. He truly admired the movement, even telling an art critic toward the end of his life, “If I were young, I would paint that way myself.”

Just as surprising, Greenberg was not the only member of the New York School who admired Norman Rockwell. Willem de Kooning, arguably its greatest painter, loved his pictures. When he saw Connoisseur on the Saturday Evening Post, de Kooning proclaimed, “Square inch by square inch, it’s better than Jackson!”

This was no idle remark or a snide put-down of a rival painter. Years later, he forced an art critic to study a Rockwell illustration with a magnifying glass to understand Rockwell’s painting skill. “See?” de Kooning said with enthusiasm, “Abstract Expressionism!”

Norman Rockwell would have appreciated that.

A strange, life-size doll is at the center of one of the Modern era’s most bizarre episodes. Its inspiration was the sudden end of an intense love affair between the Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka and the fascinating Alma Mahler.

A strange, life-size doll is at the center of one of the Modern era’s most bizarre episodes. Its inspiration was the sudden end of an intense love affair between the Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka and the fascinating Alma Mahler.

In the new layout, all Botticelli’s works have been restored and given more space. There is a fresh feeling like a newly constructed home compared to the old dark and crowded spaces. While you can’t actually smell the new paint, you can still see the marks of the suction cups used to place the glass in front of the Birth of Venus.

In the new layout, all Botticelli’s works have been restored and given more space. There is a fresh feeling like a newly constructed home compared to the old dark and crowded spaces. While you can’t actually smell the new paint, you can still see the marks of the suction cups used to place the glass in front of the Birth of Venus.

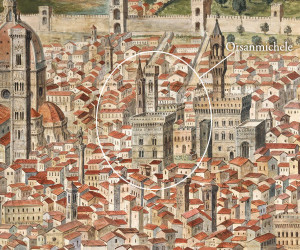

It was a stormy afternoon (not night), when I nervously entered Florence’s

It was a stormy afternoon (not night), when I nervously entered Florence’s

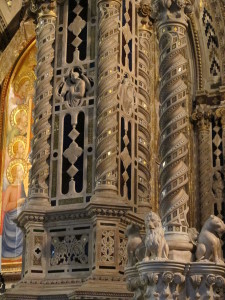

The odds were stacked against

The odds were stacked against