The opening of the Museo del Duomo in 2015. Photo: Andrea Paoletti

The reviews for Florence’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo highly anticipated reopening in 2015 after an expansion and extensive renovation were enthusiastic. The Florentines were thrilled about finally having a truly 21st century museum in their city center. But when I made my first visit that November, my reaction was very different. I was stunned by the many unaesthetic choices made by its designers, left cold by its grand gestures, and particularly disturbed about how it had intentionally eliminated the possibility of intimate contact with so many of its iconic works – like Donatello’s Magdalene – something that was a hallmark of the old museum. This past summer I returned again, hoping that my initial reaction was simply shock at seeing big changes in an old favorite museum. Yet the second visit only reinforced my disappointment and frustration.

This Fall, however, I had an extraordinary opportunity to understand the philosophy behind the changes to the Museo dell’Opera by joining a tour given to Museum Studies students. The leader of the tour was none other than its Director, Monsignor Timothy Verdon, who, I came to learn, was behind all of the design decisions for the new museum. If anyone could convince me of the wisdom of these changes – this was the man.

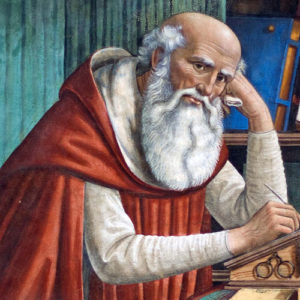

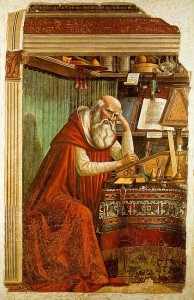

Monsignor Timothy Verdon

Timothy Verdon has had an extraordinary career. While originally from New Jersey, he has lived and worked in Florence for more than half a century. An expert on sacred art, with a PhD in Art History from Yale University, he has curated important exhibits and written many books on the subject. Today, besides being Director of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, he teaches at Stanford University’s Florence campus and is the Canon of the Florence Cathedral complex, which includes the Baptistry, Giotto’s Campanile (or Bell Tower), and the Duomo.

Our group met the Director in the lobby, which remains at the old entrance to the Museum. Msgr. Verdon greeted us with a sweet and friendly smile, acknowledging his enthusiastic introduction by a faculty member with endearing modesty. He began the tour by explaining the goals of the renovation. His words revealed the central role he had played in developing its new vision. “My vision” was to re-connect the museum with the historical sites of the Cathedral piazza. He pointed out that the Duomo museum is unlike a typical museum, since almost all of its art is from one place – the buildings of the Piazza del Duomo — the same place where it is shown. Thus, unlike almost any other major world museum, it provides a unique opportunity to talk about the place itself and to have what Verdon called a ‘narrative.’

It was a stormy afternoon (not night), when I nervously entered Florence’s

It was a stormy afternoon (not night), when I nervously entered Florence’s

The odds were stacked against

The odds were stacked against

Volume 2 of our series “

Volume 2 of our series “

![Hokusai (1760-1849) [89], Self-portrait at the age of 80](https://lewisartcafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/hokusai-selfportrait-at-the-age-of-eighty-three-187x300.jpg)