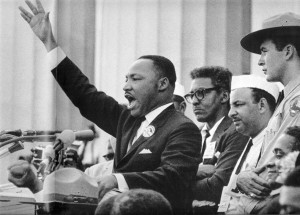

England’s greatest painter, J.M.W. Turner, is the subject of a new film by Mike Leigh. On May 15th, Mr. Turner premiered at the Cannes film festival and received rave reviews. Its star Timothy Spall won the best actor award for his portrayal of the artist. [Spall is best known in the U.S. as Peter Pettigrew or Wormtail in the Harry Potter films.]

The film covers the last twenty-five years of Turner’s life. The trailer includes a famous incident from life of the eccentric and notoriously competitive artist — when he took advantage of the Royal Academy of Art’s ‘Varnishing Day.’ In the 1800s, the Academy was the center of the British artistic world. No artist could truly succeed without being a member and no exhibition was more important for one’s reputation than the annual Summer Exhibition.

Joseph Mallord William Turner was one of the few child prodigies in the history of art. One year after he began classes at the Academy, he was made a member of the Academy. He was only 15. By the time he was 17 he could support himself with the sale of his pictures. In comparison, the great landscape painter, John Constable, who was about the same age as Turner, struggled financially his entire life and didn’t earn membership until he was 53.

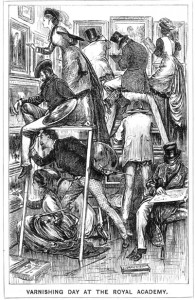

The Varnishing Day incident concerns both painters. The day was a tradition at the Royal Academy. Each year after the Summer Exhibition was hung by the jurors, artists were allowed inside to put the final protective varnish on their paintings before the show opened. This was not just a necessary stage in finishing a work but a bit of a social event. The tradition continues to this day and the entrance of the artists includes a parade, a religious service, canapes and champagne. Once inside, the painters chat amongst themselves as they apply their varnish and a few last touches.

Just as important as putting a protective layer on a painting, Varnishing Day allowed the artists to preview the exhibition before it opened to the public and to learn whether their pictures had been hung in a good location and discover whose work was hung nearby. While it was an honor to be chosen, if your picture was put very high up or to the side of a doorway, it meant the jurors did not consider it an important picture, which could damage your reputation.

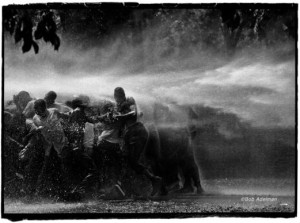

In 1832, both Turner and Constable’s pictures were hung in good positions, but unfortunately next to each other. Constable’s Opening of Waterloo Bridge was the largest painting he had ever painted for an exhibition, nearly seven feet long. He had worked on it for thirteen years. When Turner arrived on Varnishing Day and saw his painting next to Constable’s, he began pacing, disturbed not only by its commanding size but by how exciting and colorful the Constable painting was.

As a fellow member of the Academy, Charles Robert Leslie personally observed:

Constable’s Waterloo seemed as if painted with liquid gold and silver, and Turner came several times into the room while [Constable] was heightening with vermilion and lake the decorations and flags of the city barges. Turner stood behind him, looking from the Waterloo to his own picture, and at last brought his palette from the great room where he was touching another picture, and putting a round daub of red lead, somewhat bigger than a shilling, on his grey sea, went away without saying a word. The intensity of the red lead, made more vivid by the coolness of his picture, caused even the vermilion and lake of Constable to look weak.

Constable was horrified at this breach of Varnishing Day etiquette and said to Leslie after Turner left, ‘He has been here…and fired a gun.’ He knew the damage had been done. Turner’s painting and its bold red spot at the center would command the attention of anyone walking into the Painting Gallery. Turner returned to the room later. With a swipe of a rag, he trimmed the red ‘gob’ and declared it a buoy.

This flourish was greeted with applause by his fellow artists. At least, according to the movie. Mr. Turner opens October 31st in the U.K. and December 19th in the U.S.