J.M.W. Turner, Burning of the Houses of Parliament, 1835. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Oddly, one of J.M.W. Turner‘s greatest subjects, the Burning of the Houses of Parliament, was the result of the modernization of accounting.

According to the October 17, 1834 issue of the Times of London:

“Shortly before 7 o’clock last night the inhabitants of Westminster…were thrown into the utmost confusion and alarm by the sudden breaking out of one of the most terrific conflaglarations that has been witnessed for many years past…The Houses of the Lords and Commons and the adjacent buildings were on fire.”

The inferno was not an act of terrorism, but a result of human error – overloading a furnace with too much wood. The wood was not ordinary fire wood, however. Two cartloads of tally sticks have been jammed in the furnaces of the House of Lords by an impatient workman.

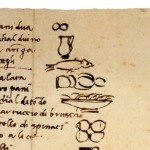

Tally sticks were one of the earliest accounting methods, perhaps going as far back as the Stone Age. Debts were marked with cuts on a thin piece of wood, the depth of a cut corresponding to the seriousness of the debt. After the cutting was complete, the stick was split lengthwise. The loaner was given the longest part (or ‘stock‘ — the source of the word, “stockholder”), the debtor getting the smaller half or, in essence, “the short end of the stick.”

Tallying didn’t require literacy and was tamper-proof. No notches could be added later by an unscrupulous money-lender because the halves wouldn’t match. As an extra safety measure, one could check that the grain of the wood across the parts tallied.

English tally sticks.

In England, the official use of tally sticks went back nearly to William the Conqueror. His son, King Henry I, established the system when he took the throne in 1100 AD and expanded its use to the collection of taxes (by sheriffs, like the villainous Sheriff of Nottingham). For more than 700 years, the British Empire’s financial backbone depended on these thin slices of wood, so accuracy was critical. The Chancellor of the Exchequer prescribed the following system of cuts:

“The manner of cutting is as follows. At the top of the tally a cut is made, the thickness of the palm of the hand, to represent a thousand pounds; then a hundred pounds by a cut the breadth of a thumb; twenty pounds, the breadth of the little finger; a single pound, the width of a swollen barleycorn; a shilling rather narrower than a penny is marked by a single cut without removing any wood”.

The tally stick system was abolished in 1826 and replaced by paper notes backed with gold controlled by the new Bank of England (though in some small European towns, tally sticks continued to be used into the twentieth century).

But how did they cause such a terrible fire eight years later? We’ll let Charles Dickens explain:

…In 1834 it was found that there was a considerable accumulation of them; and the question then arose, what was to be done with such worn-out, worm-eaten, rotten old bits of wood? ….The sticks were housed in Westminster [Parliament], and it would naturally occur to any intelligent person that nothing could be easier than to allow them to be carried away for fire-wood by the miserable people who lived in that neighbourhood. However, they never had been useful, and official routine required that they should never be, and so the order went out that they were to be privately and confidentially burnt. It came to pass that they were burnt in a stove in the House of Lords. The stove, overgorged with these preposterous sticks, set fire to the panelling; the panelling set fire to the House of Lords; the House of Lords set fire to the House of Commons; the two houses were reduced to ashes…

Turner, The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 1834, watercolour study (Tate Gallery, London)

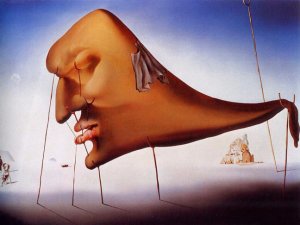

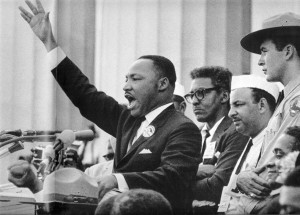

J.M.W. Turner was one of the tens of thousands of Londoners who lined the south bank or crowded onto bridges across the Thames River to witness the burning of the Houses of Parliament. He filled two sketchbooks. He made drawings and watercolors from several positions, even hiring a boat to take him down the river. He would complete two oil paintings in his studio based on the national tragedy,earning him the nickname ‘the fire King.’

Detail of The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons (Philadelphia Museum) Photo: Wayne Stratz/Flicker

Once can easily see why the scene so captivated Turner, a man who believed in nature’s sublime and terrible magnificence. What a subject for a Romantic artist! The brilliant fire’s golden light illuminates the night, sending sparks across the canvas, reflecting in the water below, framed by a vortex of billowing clouds of smoke. What better symbol of the awesome power of nature, one that makes the hordes of people who line the edges look quite small and insignificant? The sturdy and impressive Westminster Bridge on the right appears to disappear near the hellish blaze. The Houses of Parliament, a symbol of Western civilization and government, are no match for nature’s fury and seems puny in contrast to the flames. These grand Gothic buildings that had housed the British governing body for centuries (and English kings before them), the center of the great British Empire, are quickly swept away.

Rebuilding took thirty years and millions of pounds. Turner, as well as the architects, would not live to see construction completed. In a strange irony, the terrible fire resulted, not just in a masterpiece of Romantic painting, but in the creation of London’s most famous symbol, the new Parliament’s clock tower by Augustus Pugin, known today around the world as ‘Big Ben.’

Note: Mr. Turner, Mike Leigh’s biographical picture on the great English painter, opened in the U.S. on December 19th and continues to receive excellent reviews.