Be careful when you insult an artist. You may be making art history.

Art criticism is probably as old as art itself and often comes in harsh tones. Plato was no friend of artists, describing them as tricksters and called for their banishment from his Republic. Yet more than once a critic’s insult has ended up naming an art movement.

In 1874, Louis Leroy wrote about an exhibition of a group of artists that included Monet, Pissarro, Degas, and Renoir, who called themselves Le Société anonyme. In a mocking tone, Leroy said of Monet’s Impression: Sunrise,

Impression; I was certain of it. I was just thinking that as I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it. And what freedom! What ease of handling! A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more highly finished than this landscape!

At the end of the review, Leroy pretends he saw a mad admirer dancing around the painting, singing ““Hi-ho! I am impression on the march, the avenging palette knife…”

The article was called “The Exhibition of the Impressionists.” The name stuck.

The new name didn’t help much with the critics. Their second exhibition in 1876 was described by Albert Wolff as “a horrifying spectacle. Five or six lunatics, one of who is a woman [Berthe Morisot], a group of unfortunates, afflicted with the madness of ambition…who call themselves…’The Impressionists,’ take a canvas, some paint and brushes, throw some tones haphazardly on to the canvas, and then sign it.”

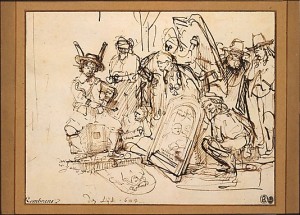

Rembrandt, Satire on Art Criticism, 1644.

The art critic, at left, is given the ears of an ass. Based on a drawing by the Renaissance artist Mantegna, which included the figures of Deceit, Ignorance, and Slander, too.

Until the twentieth century, when art historians described the art of the 1600’s as Baroque the term was not meant to be just a neutral name for an art historical period. Derived from a Portuguese or Spanish word meaning “an irregular pearl,” the term was used to criticize the elaborately decorated and ‘excessively’ dramatic art styles that art historians thought had “perverted” the idealistic beauty of the Renaissance. Another source for “Baroque” is an old philosophical term that means ridiculous or strange.

There can be no harsher critic than a fellow artist. In the early stages of his competition with Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse meant it as an insult when he described the younger man’s paintings as “Cubism.”

Matisse himself had already experienced this strange phenomenon in 1905, after a review of an exhibit of his paintings, along with those of André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck. The show was denounced as an “orgy of pure tones,” by the critic Louis Vauxcelles. But when Vauxcelles described a conservative statue in the midst of the gallery as a “Donatello among the fauves (wild beasts),” he had no idea he had just named the new movement.

Coincidently, three years later Vauxcelles described a painting of houses on a hill by Picasso’s comrade Georges Braque as being made of cubes. That probably is what was in Matisse’s mind when he insulted and named the movement that soon swept Paris and supplanted his Fauves as the darling of the avant-garde.

The rest, as they say, was history. Art history.