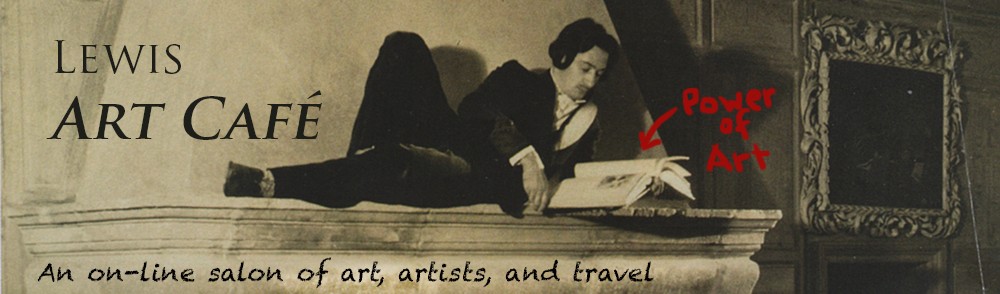

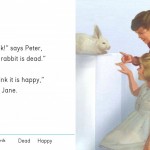

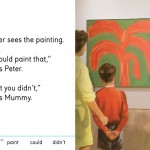

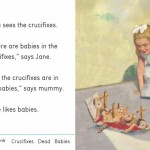

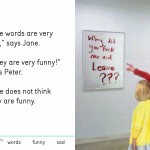

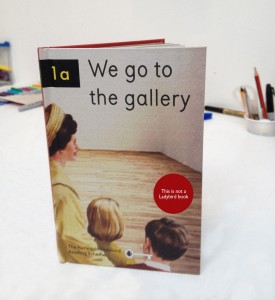

Miriam Elia, a British artist and comedian, and her brother, Ezra, recently published We Go to the Gallery, a book on art that parodies contemporary art in the style of a children’s first reader in England. The publishing giant Penguin want to destroy all copies of it.

Miriam Elia, a British artist and comedian, and her brother, Ezra, recently published We Go to the Gallery, a book on art that parodies contemporary art in the style of a children’s first reader in England. The publishing giant Penguin want to destroy all copies of it.

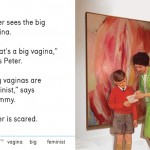

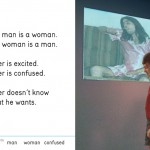

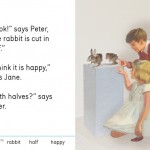

Like the Dick and Jane books in the U.S., England has the Peter and Jane series published by Ladybird, a division of Penguin Publishing. In Elia’s book, Peter and Jane go to look at contemporary art in a gallery with their mother. Funds to publish the book were raised using Kickstarter and she printed 1,000 copies.

According to Penguin’s lawyers, the book violates the publisher’s copyright. They are willing to allow Elia to sell enough books to pay off her costs as long as she burns the remaining copies herself or turns them over to them, so they can destroy them.

Elia is refusing “to bend to their depravity” in a statement that ends with:

They will never find the books they seek to pulp, and if they take me to court, I will fight them, however long the battle takes. But I am need of your help. If you like the work and wish to see it properly published, please email wegotothegallery@gmail.com. I will shortly be starting a petition, and may have to devise a fighting fund to help with legal costs.

The full statement can be found on Elia’s website.

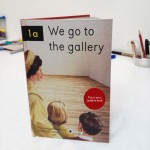

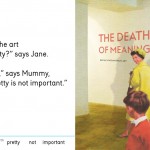

Below is a gallery of some of the pages of Elia’s book. (Click on an image to see a slide show.) Take a look while you still can.

- “We go to the gallery” cover