Joseph No Two Horns, He Nupa Wanica (Hunkpapa Lakota), Horse Effigy, c. 1880. Wood (possibly cottonwood), pigment, commercial and native-tanned leather, rawhide, horsehair, brass, iron, bird quill. Length: 38 1/2 in. South Dakota State Historical Society, Pierre.

Joseph No Two Horns‘s Horse Effigy is not only a powerful sculpture, but a portrait of a beloved horse ridden to victory in the Battle of the Little Big Horn. In a recent exhibition of Plains Indian art with hundreds of objects at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, it regularly drew the biggest crowds. His horse’s death in that battle haunted the artist for the rest of his life.

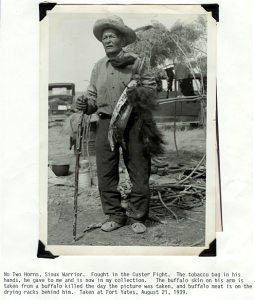

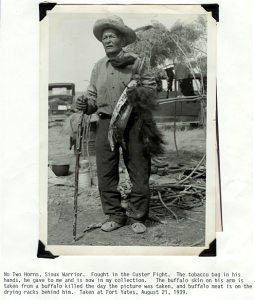

Joseph No Two Horns, 1939. Notes from Colonel A.B. Welch.

In 1876, No Two Horns or He Nupa Wanica, was a 24 year old Hunkpapa Lakota warrior following his chief and cousin, Sitting Bull, when he fought in the most famous battle of the Great Sioux War. Popularly known as Custer’s Last Stand, it is called The Battle of Greasy Grass by the Lakota. On June 25th, General George Armstrong Custer and his Seventh Cavalry were scouring the Montana territory looking for about 800 “hostiles” as reported by his scouts. Custer expected to easily drive them back into their reservations. Instead, when the Seventh Cavalry attacked what they thought was a small village, Custer and his men found themselves facing the combined forces of thousands of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors.

Joseph No Two Horns, Death of Blue Roan Horse. c. 1876. Drawing on paper, 8 x 10 “. State Historical Society of North Dakota.

In the battle, No Two Horns’s blue roan suffered seven bullet wounds before collapsing, but not before carrying No Two Horns to victory over the army of General George Custer. For the rest of his life, until his death in 1942, he portrayed this event in colorful drawings and paintings, as well as sculptures.

This wooden sculpture from 1880 shows his galloping horse is in the midst of battle. It stretches and strains, fighting to keep moving as death nears. His eyes are brass tacks, his leather ears are pulled back. Bullet wounds across his body run red. His mouth is covered in blood and red dyed horse hair dangles to represent blood running from his mouth. Like a skilled animator, No Two Horns pulls the horse’s torso into the long line of its motion path.

This wooden sculpture from 1880 shows his galloping horse is in the midst of battle. It stretches and strains, fighting to keep moving as death nears. His eyes are brass tacks, his leather ears are pulled back. Bullet wounds across his body run red. His mouth is covered in blood and red dyed horse hair dangles to represent blood running from his mouth. Like a skilled animator, No Two Horns pulls the horse’s torso into the long line of its motion path.

The love of horses is an important part of Plains culture and one of the many atrocities of General Custer’s Seventh Army was their systematic slaughter of Plains Indian ponies. The Lakotas were a warrior society and these effigies or Dance Sticks were used in ceremonies and dances to prepare for battle or celebrate victories. This is, however, the only existing Dance Stick that shows the entire body of a horse.

No Two Horns remains one of the most famous artists of the Plains Indians and his effigies the model for many other Plains artists. Today, his Horse Effigy is not only the most prized object in the collection of the South Dakota State Historical Society but their symbol.

No Two Horns remains one of the most famous artists of the Plains Indians and his effigies the model for many other Plains artists. Today, his Horse Effigy is not only the most prized object in the collection of the South Dakota State Historical Society but their symbol.

While a veteran of more than forty battles, Joseph No Two Horns did not brag about his exploits. In 1926, No Two Horns participated in the ceremonies honoring the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of the Little Big Horn. He said he danced for the ‘soldiers who were so brave and foolish.’

[Thanks to Danyelle Means for corrections to this story.]

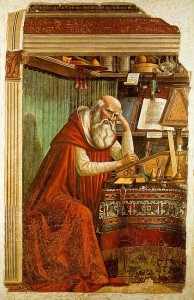

In the new layout, all Botticelli’s works have been restored and given more space. There is a fresh feeling like a newly constructed home compared to the old dark and crowded spaces. While you can’t actually smell the new paint, you can still see the marks of the suction cups used to place the glass in front of the Birth of Venus.

In the new layout, all Botticelli’s works have been restored and given more space. There is a fresh feeling like a newly constructed home compared to the old dark and crowded spaces. While you can’t actually smell the new paint, you can still see the marks of the suction cups used to place the glass in front of the Birth of Venus.

It was a stormy afternoon (not night), when I nervously entered Florence’s

It was a stormy afternoon (not night), when I nervously entered Florence’s

The odds were stacked against

The odds were stacked against

Volume 2 of our series “

Volume 2 of our series “

![Hokusai (1760-1849) [89], Self-portrait at the age of 80](https://lewisartcafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/hokusai-selfportrait-at-the-age-of-eighty-three-187x300.jpg)