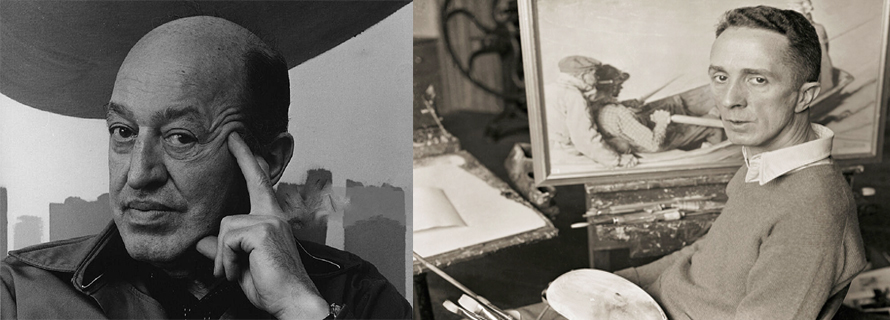

After World War II, the center of the art universe shifted and New York City replaced Paris as the home of the avant-garde. In Manhattan’s downtown bars and studios, passions ran high. Arguments about art and ideas often turned into celebrated drunken brawls. Amidst the turbulent turf wars, one art critic reigned supreme – Clement Greenberg. His discovery of Jackson Pollock led to the rise of Abstract Expressionism as the dominant art form in the post-war art world. His opinions were followed intensely, even feared, by artists, dealers, and collectors.

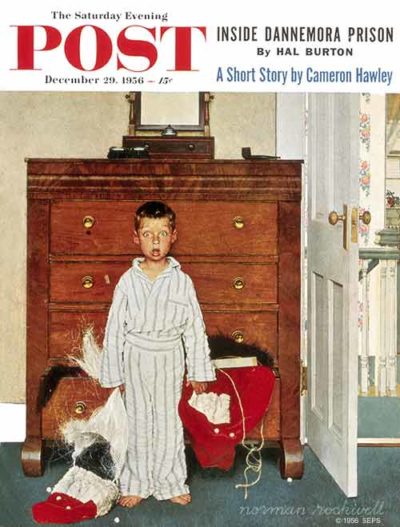

Yet, despite the New York School’s position as the foremost movement in Modern Art, if you asked most Americans in the 1950s to name their favorite artist, they would probably have said Norman Rockwell, the beloved illustrator of covers for the Saturday Evening Post. For decades, the Post had been the most popular magazine of its time. Self-proclaimed as “America’s Magazine,” its covers depicted an ideal small-town America, not unlike the New England towns where Rockwell spent most of his adult life. In fact, his models were often his neighbors. His covers were regularly turned into posters and found their way onto the walls of homes across the country.

This frustrated Clement Greenberg, who was justifiably proud of the emergence of New York as the global center of art. In his best-known essay, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” he struggled to understand how such a strange state of affairs was possible and why the citizens of his country were not embracing their great cultural victory. At the end of its very first sentence, he almost calls out Rockwell by name:

“One and the same civilization produces simultaneously two such different things as a poem by T. S. Eliot and a Tin Pan Alley song, or a painting by Braque and a Saturday Evening Post cover.”