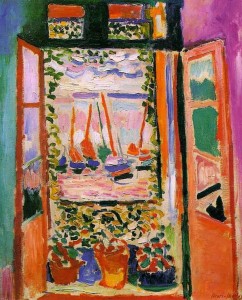

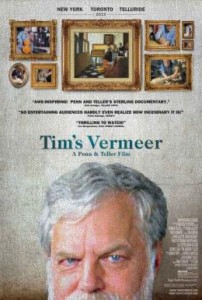

Henri Matisse

French Window at Collioure, 1914

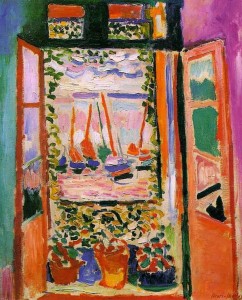

French Window at Collioure is the closest Henri Matisse ever got to painting a totally abstract work. Without the title, the painting is hard to see as more than three simple bands of color framing a large black center. The mood is somber and calm. But what is behind this picture?

The subject is one that Matisse had already painted many times. For nearly a decade, when Paris became cold and wet, he had returned to his rented studio in Collioure, a town near the Spanish border in the south of France. Its window looked out on the town’s harbor.

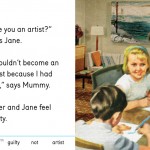

- Matisse, Open Window, 1905

The most famous version is perhaps the first — 1905’s Open Window, which became the iconic image of Fauvism. It conveys the visual excitement Matisse felt that summer when he first discovered the town and the light of the South of France. The light triggered a new movement that became known as The Fauves (‘the wild beasts’). He and his colleagues, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, reacted with violent colors that went beyond what even their beloved van Gogh had used in Provence. [Vlaminck said he loved van Gogh more than his father.] Matisse described the colors they applied unmixed in raw fashion on the canvases as ‘explosives.’ His ‘co-conspirator’ Derain said their paintbrushes were like sticks of dynamite.

After this period of Fauvist fireworks, Matisse’s approach evolved. He told the Futurist artist Gino Severini that he believed in an art stripped down to its essentials, simplifying an image “like you might prune a tree.” Still, 1914’s French Window is so different a view from the one of 1905 that it is hard to believe it is the same window. Why is that and why is it so unique in Matisse’s career?

Window of Matisse’s studio in Collioure

c. 1942

The picture’s date is an essential clue. The window had not changed, but the world had.

France was now at war. The Great World War had begun with great confidence but by the time the picture was painted it was a hard time to be hopeful. From the start, the French suffered great losses. News from the front was difficult to find but rumors told of millions of French soldiers killed. Matisse’s home town in the north of France was one of the first overrun by the German army. His elderly mother was in ill health and trapped behind enemy lines; his brother a prisoner of war. Matisse had to leave his own house in the suburbs of Paris after it was commandeered by French officers as a military headquarters. His fellow Fauvists, Derain and Vlaminck were drafted. Matisse, though he tried to enlist several times, was rejected because he was already in his mid-forties.

Henri Matisse,

c. 1913

In Collioure, Matisse opened his house to refugee artists like the Spanish Cubist, Juan Gris. The young Gris’s poverty (his dealer could no longer provide his small stipend) reminded Matisse of his own early days as an artist. Matisse was also without the support of his gallery, so he went to his friend, the American patroness, Gertrude Stein. Happily, she agreed to help Gris out with some income. When the funds never arrived and there was no explanation, it was the end of Matisse’s friendship with her.

Rather than a colorful harbor of swaying sailboats, The French Window of 1914 opens onto blackness. Matisse’s search for “an art of balance, of purity and serenity” is fruitless here. There is some balance, but it is not firm, only tentative. The sketchy marks of the window shutter at left reflect anxiety, the painful uncertainty of wartime. His colors are muddied with grays, uncharacteristically subdued.

What is arguably the most radical painting Matisse ever painted never saw the light of day during his lifetime. When it was finally exhibited in the U.S. in 1966, it was already well after the American Abstract Expressionists had created their even more radical abstract revolution. The art world was well prepared to greet French Window at Collioure with some surprise perhaps, but mostly admiration.

The painting, however, expands our understanding of one of the great masters of the twentieth century. Matisse’s reputation is as a painter whose modernist vision resulted in largely comfortable, colorful pictures of bourgeois or exotic interiors, cut off from the concerns of politics and current events. Yet, the French Window of 1914 is an existential statement by an artist caught in a world blackened by war. It is Matisse’s Guernica, painted a generation and world war earlier than Picasso’s.

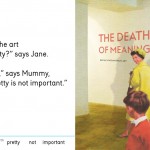

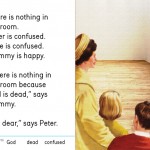

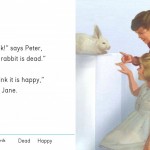

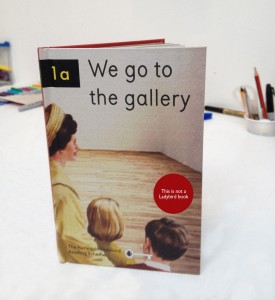

Miriam Elia, a British artist and comedian, and her brother, Ezra, recently published We Go to the Gallery, a book on art that parodies contemporary art in the style of a children’s first reader in England. The publishing giant Penguin want to destroy all copies of it.

Miriam Elia, a British artist and comedian, and her brother, Ezra, recently published We Go to the Gallery, a book on art that parodies contemporary art in the style of a children’s first reader in England. The publishing giant Penguin want to destroy all copies of it.