Volume 2 of our series “Truly Old Masters” focuses on Modern and Contemporary artists who lived long and fruitful lives in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (except Americans, who will be the subject of Volume 3). Since medical care improved considerably after 1900, it has become more and more common for artists to live to a ripe old age. That’s why for this volume we’ve raised the bar from 75 to 80 years old. Still, the list is long, even though it covers not much more than a century.

Volume 2 of our series “Truly Old Masters” focuses on Modern and Contemporary artists who lived long and fruitful lives in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (except Americans, who will be the subject of Volume 3). Since medical care improved considerably after 1900, it has become more and more common for artists to live to a ripe old age. That’s why for this volume we’ve raised the bar from 75 to 80 years old. Still, the list is long, even though it covers not much more than a century.

While there are plenty of artists who worry about aging, many celebrate it as an opportunity to do more and better work. To congratulate the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman on reaching his 70th birthday, the 77 year old film-maker Akira Kurosawa wrote to him about an artist who “bloomed when he reached eighty.” Kurosawa, who lived to 88 and continued to write films almost to the end, told Bergman that he realized his own work “was only beginning” and that artists are “not really capable of creating really good works until [they] reach the age of 80.”

Louise Bourgeois in 2009

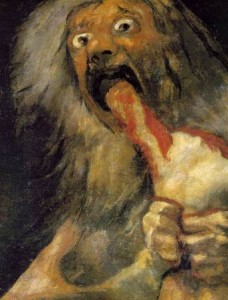

Recent studies are debunking the old theories that great artists (and scientists, for that matter) do their best work by the time they are thirty. The sculptor Louise Bourgeois who lived nearly to 100, described herself as a ‘long distance runner.’ When she was 84, she was asked whether she could have made a recent work when she was younger. She replied, “Absolutely not.” When asked why, she explained, “I was not sophisticated enough.”

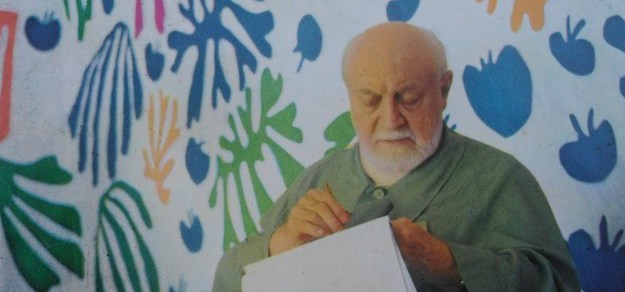

Old age is not without its hazards, but even they can be inspiring. Henri Matisse suffered from a near fatal illness in his seventies. After he survived a dangerous surgery, he said,

“My terrible operation has completely rejuvenated and made a philosopher of me. I had so completely prepared for my exit from life that it seems to me that I am in a second life.”

Despite being mostly bedridden, his ‘second life’ led to the exuberant, colorful paper cut-outs that occupied him for the rest of his life.

Below is a gallery of portraits and works by twentieth century artists who did not die young but lived long enough to truly become old masters. [Click on an image to begin slide show.] Continue reading