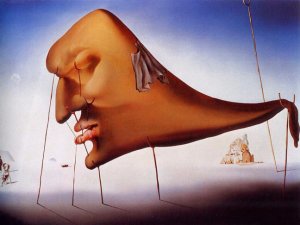

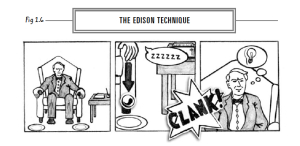

While dreams were the source of his imagery, Salvador Dalí felt that sleep was a great waste of time. Whenever he was getting sleepy, he would sit in a stiff, Spanish “bony” armchair with a metal key in his hand. Just below his hand, he placed a dinner plate. As soon as he nodded off, the key would slip out of his hand, hit the plate with a loud “CLANG!” and wake him up. According to Dalí in his 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, anyone who followed his method of “slumber with a key” would “wake up inspired!”

This kind of very brief nap is called by scientists “hypnogogic” and is known for releasing a rush of creative thoughts. Other famous nappers who believed in only sleeping a few hours a day were Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Albert Einstein, Aristotle, and Leonardo da Vinci.

Da Vinci is reputed to have had a method, known as polyphasic, where he slept fifteen minutes every four hours, never going beyond a total of five hours a day. Lord Byron, Thomas Jefferson, and Napoleon are also said to have used this approach, which causes vivid dreams.

Dalí wrote, “At the age of six I wanted to be Napoleon – but I wasn’t.” At least, he later slept like him.