In Paris’s Musée Picasso, a four-foot tall idol from the Pacific Islands sits in a glass case. Wild eyed and dramatic, with arms flung out stiffly, visitors might justifiably assume that it was one of the many native objects that Picasso kept in his studio for inspiration. But the story behind it is much more complicated. The idol was a gift from Matisse that Picasso didn’t want.

While their styles were quite different, both artists were inspired by the art of aboriginal peoples (‘primitive art’ as it was known then). For Picasso, it is well known that African art was the catalyst for his Cubist revolution. What is less well known is that Matisse collected African sculptures even before Picasso. In fact, he was the person who introduced Picasso to one of them at a soirée in Gertrude Stein‘s apartment in Paris in 1906.

According to Max Jacob, a friend of Picasso, who was there that evening,

Matisse took a wooden statuette off a table and showed it to Picasso. Picasso held it in his hands all evening. The next morning when I came to his studio the floor was strewn with sheets of drawing paper. Each sheet had virtually the same drawing on it, a big woman’s face with a single eye, a nose too long that merged into a mouth, a lock of

hair on one shoulder … Cubism was born.

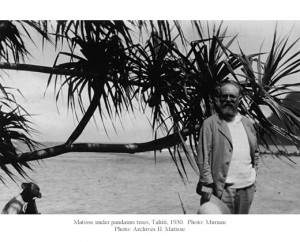

Ultimately, Matisse found the work of the Pacific peoples more to his taste. In 1930, when he was 60, he even traveled on a ship to Polynesia and lived in Tahiti for a couple of months.

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, after decades of sometimes bitter competition, Picasso and Matisse’s wary but respectful relationship had grown into an important friendship. Whenever the old rivals met together in the South of France, they discussed what they were working on and from to time exchanged gifts and paintings. Since Matisse was twelve years older than Picasso, there was an element of the mentor in their interactions — one Picasso resisted.

Matisse’s studio at Le Régina, Nice, 1953. New Hebrides mask on chair at right.

(Photograph: Hélène Adant)

When Matisse presented Picasso with the New Hebrides idol from his tour of the South Seas, Picasso could only smile and say thank you. But Francoise Gilot, Picasso’s companion at the time, noticed how Picasso’s jaws tightened as Matisse explained how he had come to own it and how it was used in rituals. In her 1990 memoir Matisse and Picasso: A Friendship in Art, she describes how she “could tell right away he didn’t like it.”

Picasso left Matisse’s studio without his gift by explaining that there wasn’t room in the car for it. As they drove away, Pablo released his anger. “Matisse thinks I have no taste. He believes I am a barbarian and that for me any piece of third-rate tribal art will do!”

When Gilot suggested they accept the gift, but put it in a room in their home where no visitor would ever see it, Picasso wouldn’t stand for it. “Certainly not!…I will not accept this awful object…If I accept the hideous gift from my so-called friend, I will have to put it in a place of honor. If I don’t our relationship is in jeopardy.”

Picasso spent much of the drive home angry and cursing. Obviously frustrated, he fretted, “I am in a bind; what am I to do?”

Gilot and Picasso decided the only thing to do was to come up with excuses whenever they went to Matisse’s home for why it was not the right time to take the idol with them. This was not so easy. Every visit they discovered that Matisse had placed the bright red, white, and blue idol in whatever room they were. Yet somehow Picasso managed to never accept the gift from Matisse.

Ceremonial Headdress, New Hebrides in Musée Picasso, Paris

Tree ferns and pandanus coated in painted clay

This is why Gilot was shocked to see it thirty years later proudly displayed in the Musée Picasso when she attended its opening in 1985. She later learned from Matisse’s son Pierre that after his father’s death in 1954, Picasso had asked him for the long postponed gift. By then Gilot had already left Picasso.

After considering this surprising news, she realized that several of Picasso’s later pictures had figures reminiscent of the wild-eyed idol. Somehow, according to Gilot, “Matisse had foreseen his friend’s further evolution” and managed to mentor Picasso — even after his own death — with an unwanted gift.