A silence of death reigned over these ruins…No clatter of vehicles, no shouts of the children, not even the song of a bird…An incredible sadness invaded our souls.

— Théophile Gautier

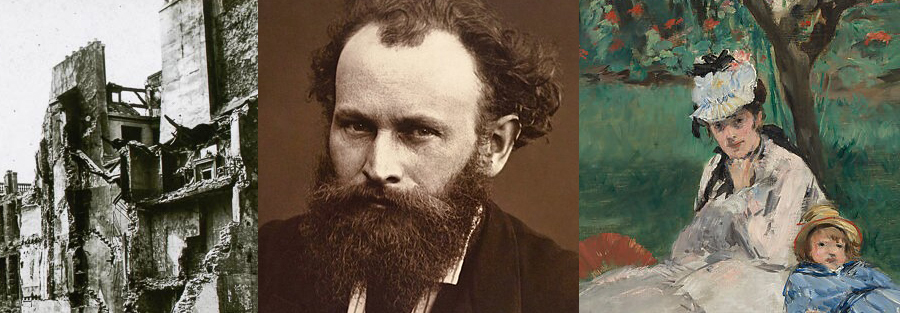

Manet looks at Civil War

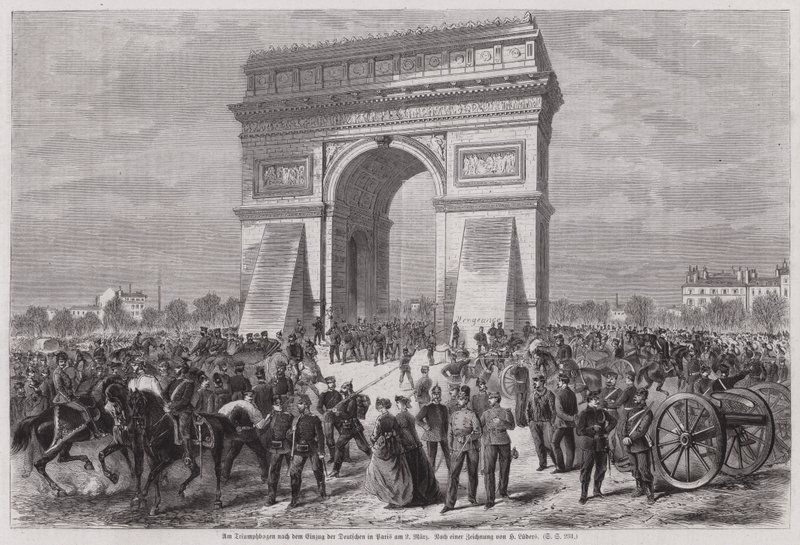

In 1872, rubble and debris could be seen all over Paris. Only a year after the disastrous Franco-Prussian war and subsequent civil war, the economy was a wreck. The city would remain a vast construction site for the rest of the decade.

Ruins of the Tuileries Palace, 1871

Because the recent events were so emotionally devastating, most French artists avoided those awful days as subject matter. But not Édouard Manet.

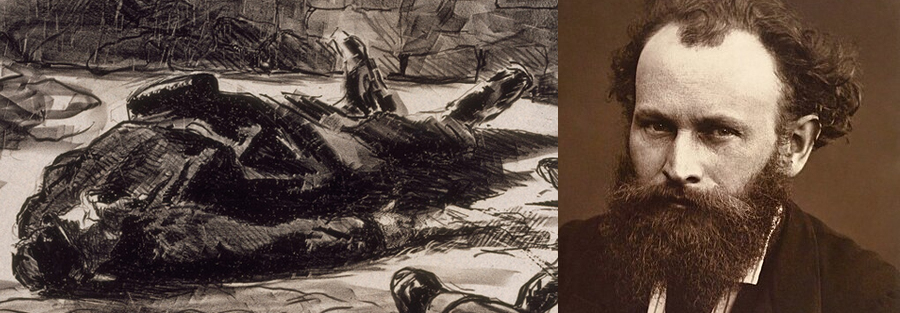

Manet, Civil War (Scene from the Commune of Paris) , 1871.

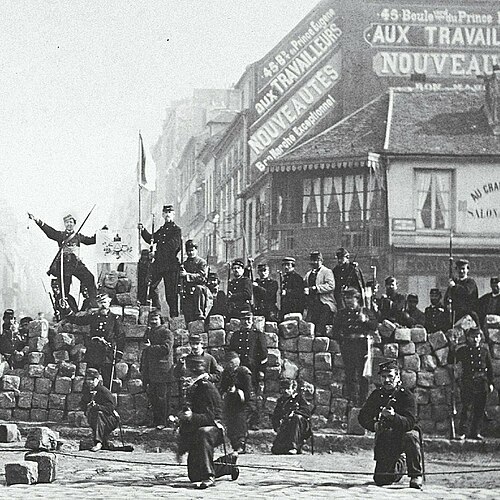

Inspired by Goya’s suite of etchings, The Disasters of War (from the early 1800s), Manet documented the suffering of the Parisians during their Terrible Year. His lithograph, Civil War (Scene from the Commune of Paris) was based on sketches he made in the grim aftermath of a battle against federal forces in late May 1871. We can see at the center a dead, heroic Communard behind a stone barricade. In the lower right corner are the legs of a civilian victim.

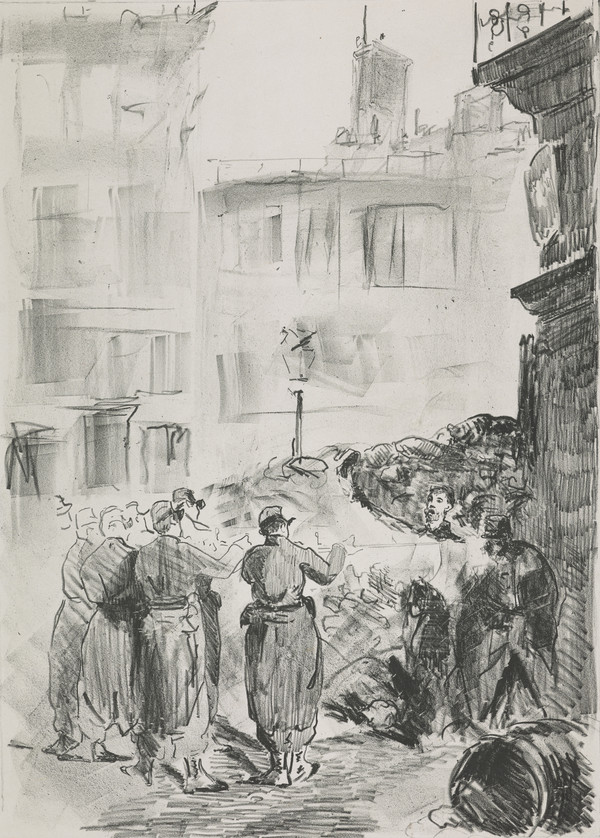

Manet, The Barricade, 1871

Manet’s The Barricade makes his reverence for Goya even more explicit. Borrowing poses from The Third of May, Manet depicts the execution of Communards by government troops at the end of the Siege. Like Goya, he feels obligated to witness the atrocity.

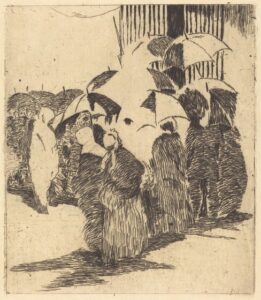

Manet, Line in Front of the Butcher Shop, 1870

Just as the Spanish artist hid his etchings, Manet kept these prints, along with his earlier Line in Front of the Butcher Shop, from the public eye. While Civil War would be published in 1874, Butcher Shop and Barricade, which showed French soldiers firing on French civilians, would, like Goya’s etchings, not be released in the artist’s lifetime.

Manet understood that pictures depicting the Siege of Paris would not be appreciated by French officials or even his traumatized countrymen.

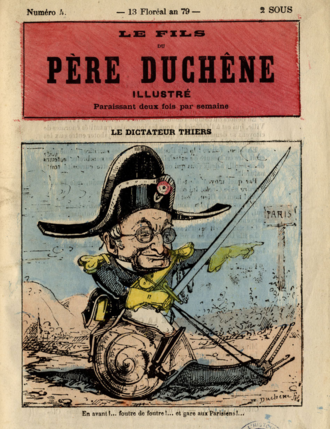

The Return of the Salon

As part of a governmental effort to return cultural life to normal, the first Salon after the Bloody Year was announced in January 1872, only 7 months after the surrender of the Paris Commune. It would be one of the most conservative in years. The Academy’s judges, appalled by the radical spirit seen in the streets of Paris, put out a call for history paintings that celebrated French patriotism, culture and traditions. This reflected the post-war spirit of the art establishment. When the Gazette des Beaux-Arts resumed publication a few months earlier, its editor declared:

Today, called by our common duty to revive France’s fortune, we will devote more attention to…art’s role…in the nation’s economy, politics, and education…we will struggle for the triumph of those teachings that will help the arts rebuild the economic, intellectual, and moral grandeur of France.

The result was a Salon that tiptoed around the recent terrible trauma in the most academic way – with symbolic, allegorical, and nostalgic scenes of noble France’s past.

Even so, not long after it opened, the President of France had seven works removed from the exhibition because they “touched too directly…on the events of the last war.”

An uncontroversial Civil War

With its March deadline approaching quickly, Manet, like most artists who had been swept up in the past year’s war and rebellion, did not have many new paintings to submit to the Salon of 1872. So, he reached back into the work he had stored for safety at the start of the war. Being Manet, he ignored the instructions of the jury and decided his entry wouldn’t be a scene from the glorious French past.

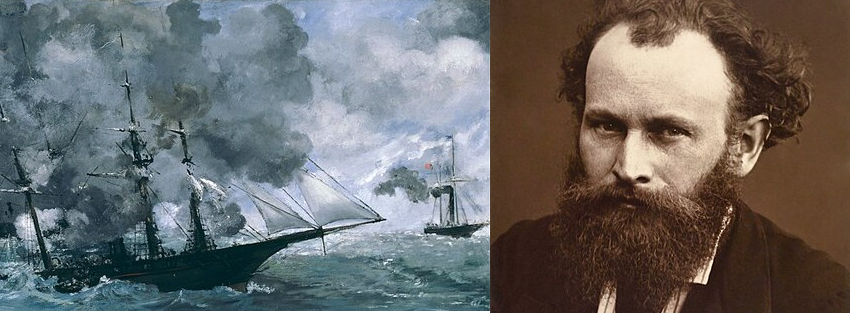

Manet, The Battle of the U.S.S. Kearsage and the C.S.S. Alabama, 1864

He chose a Civil War battle scene, but not one fought by the French — his The Battle of USS Kearsage and the CSS Alabama from 1864. Of course, a painting of civil war was still a bit provocative, since the rebellion in Paris was just a few months earlier and still on everyone’s minds.

Luckily for Manet, the judges did not make the connection and accepted Manet’s exciting “historical” sea battle for the Salon of 1872. And, unlike his infamous paintings of the 1860s (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia), this canvas even earned him some positive reviews. Viewers talked of its “grandeur;” one critic calling it a “magnificent marine painting.”

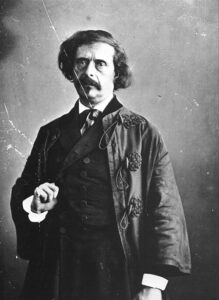

Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, photo by Nadar

The most enthusiastic review was written by Jules Barbey D’Aurevilly, an important writer and critic. Writing about the Salon for Le Gaulois, he declared “Among all the graphic artists, only one has conveyed to me a powerful feeling for Nature…You will be a little astonished, just as I was. I am going to talk of Édouard Manet.

D’Aurevilly was well acquainted with the artist’s reputation. “According to some, Monsieur Édouard Manet has no talent…According to others he is a man of genius (no less!)…”

What he couldn’t deny was that he “was moved by this picture of The Battle of Kearsage and the Alabama in a way which I never believed Monsieur Manet capable of inspiring.” The picture according to D’Aurevilly “contains everything that is most natural and primitive within the scope of any paintbrush since the world began…He has cast a ring into the sea, and I swear to you that the ring is golden.”

For the very first time, critics who were not Manet’s personal friends embraced his subject matter and seemed impressed with his skills as an artist. These reviewers seemed to overlook what previous critics could never ignore – the painting’s lack of finish and loose, suggestive brushwork. But Manet’s quick, energetic paint strokes did draw the attention of his younger admirers; artists who were about to make their own mark on art history.

The Birth of Impressionism

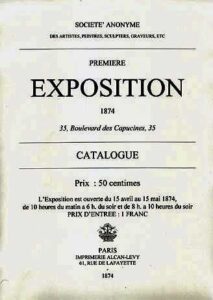

Two years later, in 1874, like a flower emerging from rubble, Impressionism (as well as its name) was born in Paris. The group of young artists called themselves the “Société Anonyme,” a standard French designation for an incorporated business. Their first exhibition was meant to be seen as a rebellion against the old French salon system.

The idea of an exhibition of “The New Painting” was first proposed by Frederick Bazille in 1867, but he would not live to see it, dying in battle during the Franco-Prussian War. Among the friends who would take up his idea were some who later became the greatest names in 19th century French painting – Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cezanne. The newly formed organization rented the famous photographer Nadar’s commercial space in the center of Paris, across from the Seine and not far from Notre Dame.

Nadar’s studio in Paris

Like a business, the Société had a charter, which gave equal rights to male and female members. Degas, who played a key role in organizing the exhibition, invited Berthe Morisot to exhibit; she would exhibit in this and all the subsequent exhibitions of the group. She tried to get Manet – a hero to the other artists and now her brother-in-law — to join them.

Manet refused and, in fact, would never exhibit with the rebels. His decision made no sense to his fellow painters and particularly upset Degas, beginning a rupture in their long friendship. He complained to their mutual friend, the painter James Tissot, “Manet seems determined to remain aloof; he may come to regret it.” Degas was convinced it was time for an independent exhibition to establish their new Modern movement. “Manet doesn’t understand…I definitely think he is more vain than intelligent.”

Manet was well acquainted with the close-minded conservatism of the Salon juries, but he still could not give up hope of reforming the Salon approach from within. For him, the annual official exhibition remained the only meaningful path to success and, ultimately, public acceptance. Despite its limited view of art, the Salon drew huge crowds and generated sales. To put this in perspective, the first radical exhibition of the young Impressionists was considered a surprising success with a total of 3,500 visitors during its 4-week run. The Salon drew more than that on any weekday and 40,000 people every Sunday.

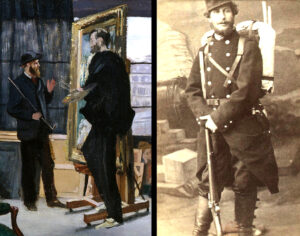

Degas, Manet Standing, 1868

Manet’s rejection of Degas’ invitation was not kind. He called his friends’ proposed exhibit a “civil war.” With even less tact, since they had fought and suffered the artillery bombardments together during the Siege, he described the rebellious exhibition as “an idiotic war if ever there was one [and] unfortunately you don’t have the big guns on your side.”

To his closest friend, the writer Antonin Proust, Manet confided, “I do not want to break away. I want to fight it out at the Salon.”

Catalog of the exhibition, 1874

The exhibition of the Société Anonyme opened without anything by Manet on April 15th , two weeks before the 1874 Salon. It included 200 works by 30 artists. In the spirit of the Commune, to be accessible to as many working people as possible, entrance was just one franc, the catalog only 50 centimes, and they offered extended evening hours.

Unlike the historical commemorations in the Salon, the exhibited works of the “Société Anonyme” were set firmly in the present. The message seemed to be, “this is our world today – at this moment – not an imaginary past, nor one obscured by ideology and politics.” In the minds of the artists (who called themselves “Modern”) another Salon filled with polished, mannered history paintings that glorified the past was no way to rejuvenate French society after a truly horrible war. It was time to celebrate the present.

But strangely, the “present” shown by these artists turned a blind eye to the recent trauma. Not one painting included a scene of the recent war, siege, or civil war. In the few pictures showing Paris streets, no barricades, ruins, or even rebuilding can be seen. This even though the exhibition was on a boulevard where Communards had raised barricades, and just a short walk from the ruins of the Tuileries Palace.

Pissarro, The Orchard, 1872

Not only did the artists ignore the unescapable evidence of war in the city, most chose to paint views of pastoral landscapes instead. Even when those fields had been sites of recent bloody battles, the Impressionist scenes appear as if nothing out of the ordinary ever happened there. The writer Emile Zola (whose most successful novel La Débâcle laid bare the war period) described his and his friends’ mindset when he wrote, “We rushed off into the countryside to celebrate the joy of not having to listen to any more talk about politics.”

Morisot, The Harbor, 1869

No one can blame them for turning their backs on politics. As far as the artists were concerned, government officials had led France into a series of idiotic missteps that led first to war with Prussia, then civil war. By some horrible turn of events, the typical political squabbling that was (and still is) such a part of French café life had led to real events that blew up everyone’s normal lives and destroyed much of Paris.

Reaction to the “Impressionists”

From their journals and letters, we know that the recent events were never far from these artists’ minds. Yet, in the most radical art exhibition of its time, visitors were greeted by lovely bucolic scenes of nature and an unscarred Paris, untouched by trauma.

Nevertheless, what look like sweet and lovely scenes to viewers today were torn apart by the critics as the work of unskilled renegades. What upset these reviewers had nothing to do with the choice of subject matter. It was the way the paintings were painted. For example, offended by Monet’s Impression: Sunrise, the journalist Louis Leroy wrote, “A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more finished than this seascape.” His review’s title, “The Exhibition of the Impressionists”, used the painting’s name to describe all the artists in the show and mock their new style. Famously, this insult unintentionally gave the movement its name.

Monet, Impression: Sunrise, 1872

Albert Wolff’s scathing review in The Figaro attacked the painters by linking them to the Communards of the Terrible Year. “The self-proclaimed artists call themselves the Intransigents, the Impressionists. They barricade themselves behind their own inadequacy.” For him and the other critics it was their style, their free, loose approach to painting, that was considered radical and revealed them as political subversives.

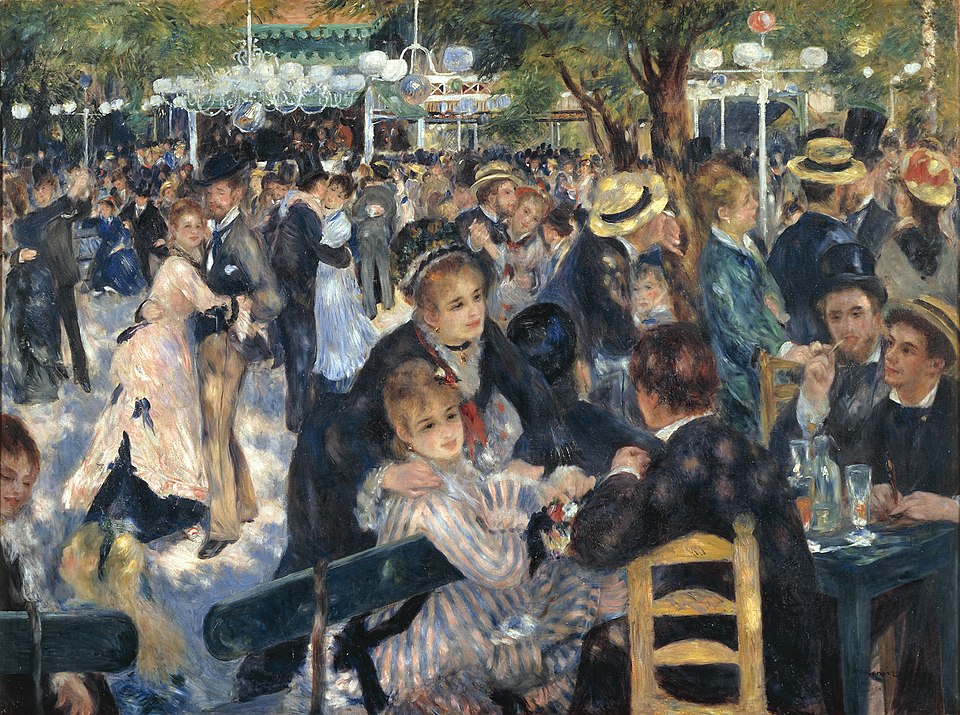

Renoir, Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette, 1876

These attacks had no effect on the artists and in the years ahead their application of paint would only become freer, as would their use of bright colors. The Impressionists’ suppression of painful memories also continued. We can see this in Renoir’s famous Moulin de la Galette of 1876, set in Montmartre, then a bit of country on the outskirts of Paris. During the fall of the Commune, the street outside of the Moulin was the scene of one of the most horrific battles of the Bloody Week. Communards were cut up by soldiers with bayonets and left dead in piles outside the doors of this very dance hall. Yet only five years later, Renoir chose this site for a scene that has come to epitomize carefree, modern French social life.

Degas, Place de la Concorde, 1875

Degas’s innovative arrangement of Viscount Lepic’s family in Place de la Concorde from 1875 is unquestionably very modern. It utilizes the unique compositions and cropping from photography that he admired. But the placement of his friend’s top hat is no accident of composition. It deliberately blocks our view of a statue in the square honoring Strasbourg, now shrouded in black to commemorate the loss of this city in Alsace to the Germans during the war.

Manet: the Reluctant Impressionist

The Salon of 1874 opened two weeks after the already notorious “First Impressionist Exhibition” and was, just as Degas expected, as conservative as all the Salons since the surrender of the Paris Commune. The jurors refused two of Manet’s three submissions.

The poet and critic Stéphane Mallarmé noted the strangeness of the jurors’ decision in La Renaissance Litteraire et Artistique and called the jury’s opinions “infantile in one sense, puerile in the other, and not totally misplaced…” Why not misplaced? Because “M. Manet does indeed constitute a danger for an Academy.”

Manet, The Railway (Gare Saint-Lazare), 1873

Ironically, the one picture chosen for the Salon — The Railway (Gare Saint-Lazare) – would have fitted better with his friends’ paintings at the exhibition going on in Nadar’s studio. Railway is an outdoor work depicting a city scene in natural light. It has no apparent political or historical references or any sign of the recent battles in the streets of Paris. Instead, we see his favorite model, Victoria Meurent, (the main figure in Déjeuner sur l’herbe and his Olympia), dressed simply and posing with a curious child in front of the railway station near his home.

Oddly, even though Manet refused to join his friends in their first exhibition (or any of the subsequent ones), most of the Paris art world seemed to have accepted without question that he was the leader of their new movement.

Manet, Stéphane Mallarmé, 1876

For example, Mallarmé in an article titled The Impressionists and Édouard Manet describes Manet as “head of the school of Impressionism.” Théophile Duret notes because of the similarity in Monet, Sisley, and Pissarro’s approaches to painting most observers “would take all their works to be those of one man – and that man, Manet.”

For Duret, he was “the precursor” and the “head of the Modern Movement.” Zola called him “the leader of the naturalist movement in painting.” Albert Wolf, the critic and antagonist of the Impressionists called him “the leader of a group of madmen.”

So, one possible reason Manet did not want to join the Impressionist exhibitions was that he understood he would inevitably be labeled their leader. Duret (who wrote the first biography of Manet) remembered the artist saying, “Je ne veux être le chef de personne” or “I don’t want to be anyone’s leader.”

In fact, the Impressionists themselves didn’t call him their leader. They did recognize his importance as someone breaking barriers for them in the Art World. By drawing the fire of art critics, he had become a kind of flag for them to rally around. It would be more accurate to say that they thought of Manet as a hero.

Pissarro called him “the first among us to dare” and “the man who made everything possible.”

Renoir said of Manet, “he was the first to establish a simple formula, such as we were all trying to find… We were all trying to paint in joyous tones and carefully eliminate all ‘literature’ from our pictures.”

For Monet, Manet’s paintings were “the revolt, freedom, new art, a breath of fresh air, life itself”.

What the Salon meant to Manet

For Manet, success and public recognition could only come via one route – the Salon. For him, “The Salon is the true field of battle — it is there that one must measure oneself.” Both Degas and Pissarro believed this was because of his vanity. After Manet’s death, Pissarro wrote to his son, Lucien, that Manet “was crazy to be recognized by the constituted authorities, he believed in success, he longed for honors …”

Another theory is that while Manet valued the works of his friends, in the first Impressionist exhibition, there were many artists whose work he did not respect and did not want to be associated with. The Impressionists we know today were not even a third of the thirty artists in their first exhibition. Their egalitarian spirit inspired them to include Louis Debras, Alfred Meyer, Léopold Robert and other second-rate artists who have all but disappeared from art history. Of course, every Salon was also filled with artists whose work Manet did not respect. But it was the Salon, which always meant a great deal to him.

Why? There may have been a deeper psychological reason behind his lifelong pursuit of acceptance by the Salon and approval by the official French art world. It is a familiar tale of a son seeking the approval of a father.

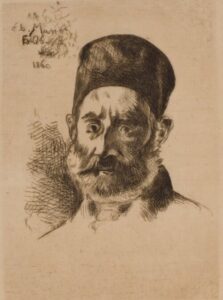

Manet, Portrait of Auguste Manet, 1860

When Manet was growing up, his father, Auguste, was a well-respected and high-ranking judge in the Ministry of Justice. Young Édouard truly admired his father and wanted to earn his respect. As the eldest son, he was expected to study the law and continue their family’s rise in French society.

But much to Auguste’s dismay, Édouard wanted to be an artist. He was totally opposed to his son’s pursuing such a career, which he did not consider a serious profession. This resulted in a covert civil war in the family. Unbeknownst to Auguste, his wife and her brother recognized the young man’s talents and were secretly encouraging him. His brother-in-law was even taking his young nephew on clandestine trips to the Louvre.

Since Édouard continued resisting legal studies, father and son compromised on a career in the Navy. Auguste sponsored a training trip in 1848 with the Merchant Marines to South America to help prepare his 16 year old for the naval entrance exams. As a seaman, the trip was not a success – Édouard failed the naval exams twice. This probably was no disappointment to the young man, since he spent his four months onboard giving drawing lessons to the sailors and producing a nice portfolio of drawings.

Manet, Man Wearing a Cloak, c. 1855 drawing

Now that a future in the Navy was out of the question, Auguste grudgingly supported his son in an art career – but only if he studied with recognized academic painters. He also funded his son’s trips around Europe to study from the Old Masters. While Auguste would never approve of his son’s choice of career, he expected his son to approach it in such a way that would bring recognition to the family — by becoming an academic artist and one day a well-respected member of the French Academy.

When Auguste Manet died in 1862, Manet took it very hard because he had not yet won the recognition and honors his father expected of him. The psychological weight of this would weigh on Manet his entire life. The only way to prove to his late father that his choice of career was the right one was to continue his pursuit of acceptance by the Salon. Something his friends and fellow artists could never understand.

Manet, Monet Family in their Garden, 1874

Because Édouard also wanted to stay true to his vision, the road ahead would be difficult. Manet’s painting after the war and Siege years would bring him even closer to the Impressionist approach. In the summer of 1874, Manet went to Argenteuil and painted side-by-side with Monet and Renoir. Their example of capturing the light with quick energetic brushstrokes loaded with fresh colors would lead to some of his most beloved pictures, like Boating.

Manet, Boating, 1874

As might be expected, this did not win him friends among the jurors of the Salon. After rejecting all his submissions in 1876, one juror said, “We have given Manet ten years to mend his ways. His not doing so — Rejected!”

A measure of official acceptance finally came to Manet in 1881. That spring he was awarded the Salon’s second-class medal for his portrait of the radical politician Henri Rochefort. An even greater honor was given to him in the fall. He was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. From this point on, he could exhibit in all future Salons without applying to the juries. Almost twenty years after his father’s death, he finally had earned accolades Auguste Manet would have valued.

Manet, The House at Rueil,1882

Unfortunately, by then Manet was quite ill and had only two more years to live. He had moved to a country villa outside of Paris with the idea it would be good for his health. Suffering from late-stage syphilis, he was unsteady on his feet, with some paralysis in his limbs. He was forced to sit while painting.

During his final illness, the landscape lost its appeal. A city lover his entire life (or as one biographer said, “always essentially Parisian”) wrote to a friend, “The countryside only has charm for those who are not forced to stay there.” His last great painting, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, from 1882, is a scene closer to his heart.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882

In the end, he would return to his beloved Paris, but for an amputation of his left leg due to gangrene. The syphilis had infected his brain, so he was unaware of the surgery. His brother Eugene wrote to Monet:

I saw him two days before his death. … it had been necessary to cut off his leg, but he hadn’t been told. When I approached his bed, he said: “Now watch out for my leg. They wanted to cut it off, but I said they mustn’t and I’ve kept it. Watch out.”

Édouard Manet died in the city he loved on April 30, 1883, at the age of 51. Fifteen hundred people attended his funeral, including Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro, and Morisot. Degas, whose friendship with Manet was the longest but also most turbulent, reportedly said at his funeral, “He was greater than we thought.”

Manet’s civil wars

Manet’s tomb, Cimitiere de Passy, Paris

In 1864, Manet found a civil war battle off French shores a fascinating and exciting artistic subject. Little did he know that in just a few years he and his fellow Parisians would find themselves swept up in the same kind of conflict themselves. Or that civil war would be a major theme in his life.

Besides the American Civil War, he would be mixed up in one on the streets of Paris, and one in the galleries. His most difficult civil war was inside himself. Throughout his career, Manet’s heart would be torn between wanting acceptance by the academics of the Salon and his need to paint the world as he saw it. He couldn’t understand what was wrong with this; he was confused by those who saw his pictures as radical and revolutionary. He said he had “no intention of overthrowing old methods of painting, or creating new ones.”

The final rapprochement between all these battling forces — the academic art world, the world he saw before him, his leadership of the modern movement, his place in art history — only came after his death. In 1934, Manet’s once scandalous Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe was finally hung in the Louvre — as his friend Emile Zola had predicted seventy years earlier.

In an article from 1864, the year Manet painted his Battle of USS Kearsage and the CSS Alabama, Zola wrote words that seemed fantastical at the time but make perfect sense today: “the future is his.”

Art historians would later go further and label him “The Father of Modernism.”

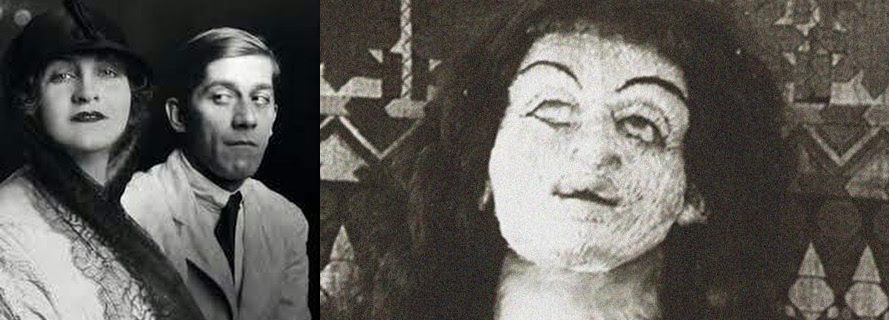

A strange, life-size doll is at the center of one of the Modern era’s most bizarre episodes. Its inspiration was the sudden end of an intense love affair between the Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka and the fascinating Alma Mahler.

A strange, life-size doll is at the center of one of the Modern era’s most bizarre episodes. Its inspiration was the sudden end of an intense love affair between the Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka and the fascinating Alma Mahler.

Marie Louise Fuller was born in 1862 on a farm outside of Chicago. As a young girl, she was inspired to be an actress by

Marie Louise Fuller was born in 1862 on a farm outside of Chicago. As a young girl, she was inspired to be an actress by

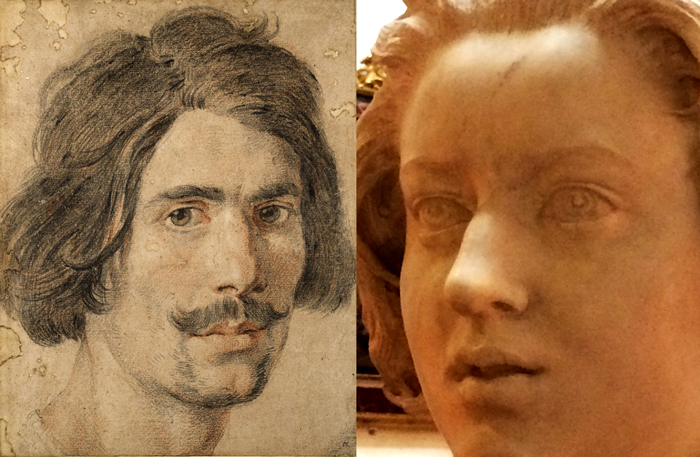

Regular visitors to Florence’s Bargello, home to its great sculpture collection, know well the frustration of finding rooms, sometimes the whole second floor, closed. Imagine my shock in June to discover that not only was the second floor open but galleries I had never seen before. In one, amidst display cases with coins, was a treasure I didn’t know existed, but learned later was quite famous and considered perhaps Gianlorenzo Bernini’s finest portrait sculpture – his bust of Costanza Bonarelli. According to the label,

Regular visitors to Florence’s Bargello, home to its great sculpture collection, know well the frustration of finding rooms, sometimes the whole second floor, closed. Imagine my shock in June to discover that not only was the second floor open but galleries I had never seen before. In one, amidst display cases with coins, was a treasure I didn’t know existed, but learned later was quite famous and considered perhaps Gianlorenzo Bernini’s finest portrait sculpture – his bust of Costanza Bonarelli. According to the label,

Around 1960, a small boy who liked to explore nature without a map was wandering in the forest near his village. He was frightened when he accidentally discovered the entrance to a cave in the woods. Later, he got up the courage to return alone from his house with a lantern. His decision to explore the cave’s passageways would take on greater meaning in the years to come.

Around 1960, a small boy who liked to explore nature without a map was wandering in the forest near his village. He was frightened when he accidentally discovered the entrance to a cave in the woods. Later, he got up the courage to return alone from his house with a lantern. His decision to explore the cave’s passageways would take on greater meaning in the years to come. A couple of years later, motivated by the huge success of video arcades, Nintendo built their own version of

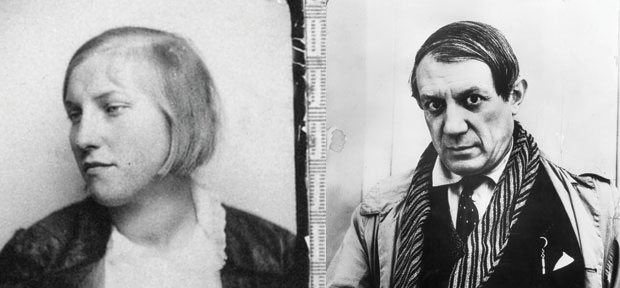

A couple of years later, motivated by the huge success of video arcades, Nintendo built their own version of  As the sun set in Paris, on January 8, 1927, Pablo Picasso was walking past a fashionable department store when his eyes fell upon a young shopper. Immediately infatuated, the artist (then unhappily married and in his mid-forties) took Marie-Thérèse Walter by the arm and said, “I’m Picasso! You and I are going to do great things together!” She was confused by the man and unaware of who he might be. Picasso introduced himself by dragging her into a bookshop and showing her a book filled with reproductions of his paintings. Thus began a passionate affair and an enormously productive period for Picasso.

As the sun set in Paris, on January 8, 1927, Pablo Picasso was walking past a fashionable department store when his eyes fell upon a young shopper. Immediately infatuated, the artist (then unhappily married and in his mid-forties) took Marie-Thérèse Walter by the arm and said, “I’m Picasso! You and I are going to do great things together!” She was confused by the man and unaware of who he might be. Picasso introduced himself by dragging her into a bookshop and showing her a book filled with reproductions of his paintings. Thus began a passionate affair and an enormously productive period for Picasso.