While at the Cleveland Art Museum earlier this month, my attention was caught by an impressive plaster head by Rodin. It was immediately familiar as a large scale version of one of the heads from his famous The Burghers of Calais, but I thought it even more moving in its own right. The marks of Rodin’s fingers as he created such a sorrowful expression were amplified by pencil marks and the traces of colored washes — I never knew Rodin did such things. But I was surprised a second time when I read the label and it said “Gift of Loïe Fuller.”

I was already aware that Loïe Fuller was an extraordinary woman. Could she be even more extraordinary than I knew?

Marie Louise Fuller was born in 1862 on a farm outside of Chicago. As a young girl, she was inspired to be an actress by Sarah Bernhardt. She found her truer calling while acting in a play, when she twirled her long white skirt in a way that suggested a rising butterfly. The audience loved it and soon she was performing across the country as a dancer in vaudeville, burlesque, and even Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Known best for her free-spirited Serpentine dance, today she is considered one of the founders of Modern Dance despite never having taken any lessons. But it wasn’t until she was 30 and crossed the Atlantic that she became one of the most famous dancers in the world.

Marie Louise Fuller was born in 1862 on a farm outside of Chicago. As a young girl, she was inspired to be an actress by Sarah Bernhardt. She found her truer calling while acting in a play, when she twirled her long white skirt in a way that suggested a rising butterfly. The audience loved it and soon she was performing across the country as a dancer in vaudeville, burlesque, and even Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Known best for her free-spirited Serpentine dance, today she is considered one of the founders of Modern Dance despite never having taken any lessons. But it wasn’t until she was 30 and crossed the Atlantic that she became one of the most famous dancers in the world.

As Loïe Fuller, she became the toast of Paris when she opened her show at the Folies-Bergère in 1892. At the center of an empty dark stage, Fuller entered in a white silk costume of her own design and then flung the material out in ever-changing huge abstract forms. Unbeknownst to the audience, inside hundreds of yards of fabric, she had sewn in bamboo sticks to push out the shapes. Colored lights, manipulated with mirrors from the sides of the stage, illuminated the billowing forms. Audiences were mesmerized by the magical metamorphosis taking place before their eyes.

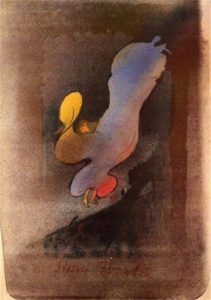

- Toulouse-Lautrec -1893. Color brush and spatter lithograph, touched with gold or silver powder

- Alphonse Mucha – 1898

- Jules Chéret – 1893