Everyone knows that there is great art in Florence, Italy. What the Taj Mahal is to India, Big Ben to London, and the Eiffel Tower to Paris, the Uffizi, Accademia, and Duomo are to this Tuscan city. Here throngs of tight-packed tourists from all over the world follow in the wake of their multilingual guides, anxious for a chance to finally see the Birth of Venus by Botticelli, Michelangelo’s David, and Brunelleschi’s Dome. Unfortunately, the Birth of Venus is hidden by a pane of glass and so badly lit that it looks better in reproductions; the David is magnificent but the space around it usually packed with other viewers. The dome of the Duomo is indeed fabulous outside and in, but disappointingly located in a cathedral from which most of the original decoration has been removed to a museum, now closed for renovation.

Everyone knows that there is great art in Florence, Italy. What the Taj Mahal is to India, Big Ben to London, and the Eiffel Tower to Paris, the Uffizi, Accademia, and Duomo are to this Tuscan city. Here throngs of tight-packed tourists from all over the world follow in the wake of their multilingual guides, anxious for a chance to finally see the Birth of Venus by Botticelli, Michelangelo’s David, and Brunelleschi’s Dome. Unfortunately, the Birth of Venus is hidden by a pane of glass and so badly lit that it looks better in reproductions; the David is magnificent but the space around it usually packed with other viewers. The dome of the Duomo is indeed fabulous outside and in, but disappointingly located in a cathedral from which most of the original decoration has been removed to a museum, now closed for renovation.

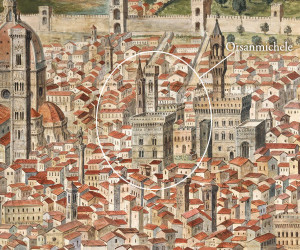

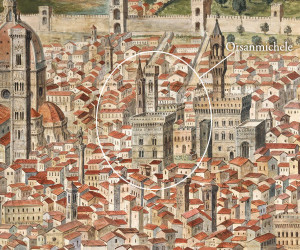

Yet Florence offers other treasures, less famous and far less crowded, but equally rewarding. In fact, although these works of art are not among those featured on 72-hour tours, they are easier to spend time viewing. In particular, we recommend three under appreciated places to enjoy art in Florence: the Orsanmichele, the Magi Chapel of the Medici-Riccardi Palace, and the Bargello. In all three, without reservations or long lines (without even an entry fee at Orsanmichele), you can spend the time it really takes to study and enjoy artwork in a peaceful setting. The three little-known artists we highlight here are Orcagna (Andrea di Cione, c.1308-1368), Benozzo Gozzoli (c.1421-1497), and Desiderio da Settignano (c.1428-1464).

Orsanmichele, Florence

Florence’s Orsanmichele is a common tourist stop, but most groups come only for a look at the famous statues on the outside by Donatello, Verrocchio, and Giambologna (ironically, all copies). Originally constructed as a place to store and sell grain, the ground floor was converted into a church in the 14th century. Here Orcagna (the leading painter, sculptor, and architect of Florence at the time) was commissioned to create a tabernacle to house a sacred image of the Madonna and Child by Bernardo Daddi. This painting replaced a fading fresco by an unknown artist, a picture of  the Virgin which had attracted its own following through miraculous powers. Not accidentally, Daddi’s masterpiece, known as the “Madonna della Grazie,” was completed in 1347, a year after the Black Death struck Florence. It is a masterpiece of Italian Gothic painting, yet not as unique as the ornate structure that frames it.

the Virgin which had attracted its own following through miraculous powers. Not accidentally, Daddi’s masterpiece, known as the “Madonna della Grazie,” was completed in 1347, a year after the Black Death struck Florence. It is a masterpiece of Italian Gothic painting, yet not as unique as the ornate structure that frames it.

The preservation and restoration of this tabernacle is so amazing that it seems to have been built in the Gothic revival style of the 19th century, not in the actual medieval period more than 650 years ago. The marble glows, the inlays of glass and lapis lazuli sparkle, the gold accents glint, reflecting the gold leaf of the halos and throne on the painting it houses. The Madonna seems to be enclosed in a tiny chapel of her own, a church within a church. Intricate yet harmonious, the carvings intersperse religious scenes and figures with decorative patterns.

The interior of the Orsanmichele is perfect for the quiet contemplation and appreciation of a Gothic masterpiece. Perhaps because Florence is primarily known for Renaissance art, Orcagna’s tabernacle (and Daddi’s Madonna) remain overlooked gems.

Our next stop, however, takes us into the Renaissance and even into the palazzo of the patrons most associated with Renaissance Florence, the Medici. The palace known today as the Medici-Riccardi, conceals within its massive walls — so typical of Florentine architecture — another uncrowded surprise.

Medici-Riccardi Palace, Florence

Benozzo Gozzoli is far from a household name in the United States, even for art aficionados. Yet this Medici palazzo owes its appeal to a single room decorated with his frescoes. The walls of the “Chapel of the Magi” (1459-61) create a magical space where the three Wise Men — here interpreted as elderly, mature, and youthful kings — their courtly followers, horses, servants, and pet animals (including a cheetah) wend their leisurely way toward Bethlehem. Dressed for display in the sumptuous brocades that made Florence wealthy, they pose attractively amidst a landscape of rocks, where a long cavalcade of of travelers climb and descend among picturesque hills and valleys. In fact, with their handsome mounts and weapons, they seem more like nobles on their way to a hunt or a joust than the mystic scholars of the bible story.

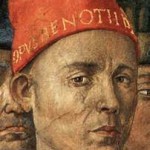

In fact, Gozzoli, a pupil of Fra Angelico and an assistant to Ghiberti, incorporated several portraits in this scene which stretches around three walls of the small chapel. Art historians don’t completely agree on the identifications, but it seems that the figure in black (below) is Cosimo the Elder (1389-1464), founder of the dynasty and patron of this work, on a modest donkey. The figure next to him, on the white horse, is his son Piero, father of Lorenzo di Medici.

Cosimo I (in black)

Other identifications are less certain. The young king has often been called an idealized portrait of Lorenzo the Magnificent, who was only a boy at the time. Another boy in the cavalcade has been called Guiliano, his younger brother who was later killed in the Pazzi Conspiracy.

The fresco even includes portraits of the artist — Gozzoli himself — one wearing a red hat, and another holding up his hand as if to say he made this work.

The Bargello, Florence

The third site we recommend for art appreciation is the Bargello, Florence’s museum of sculpture. The Bargello is to Florentine sculpture what the Uffizi is to Florence’s painting. In fact, many of its works were formerly part of the Uffizi Collection. Here you may recognize well-known masterpieces of the Renaissance by Donatello, Verrochio, and Michelangelo. We recommend that you widen the scope of your discoveries to include the work of Desiderio da Settignano.

A Renaissance sculptor who attained popularity at about the same time that Gozzoli was painting the Chapel of the Magi, Desiderio is known for particularly graceful and sensitive portraits and relief sculptures. At the Bargello, you will see his portrait of Maria Strozzi, a head of John the Baptist, and a beautiful Madonna and child — among other notable works. Once you recognize his style, you will be able to identify other sculptures as well.

A Renaissance sculptor who attained popularity at about the same time that Gozzoli was painting the Chapel of the Magi, Desiderio is known for particularly graceful and sensitive portraits and relief sculptures. At the Bargello, you will see his portrait of Maria Strozzi, a head of John the Baptist, and a beautiful Madonna and child — among other notable works. Once you recognize his style, you will be able to identify other sculptures as well.

Of the three artists we have focused on here, Desiderio is best represented in collections outside of Italy – for instance, you can find his work in the National Gallery of Art, in Washington D.C.

Great art is everywhere in Florence; these are only a few examples of where to find it “off the beaten track.” If you prefer to enjoy your art without crowds of tourists more intent on selfies than the masterpieces in front of them, we recommend venturing to one of these locations and immersing yourself in more relaxing art appreciation.