“…every war is worse than expected.” – Paul Fussell

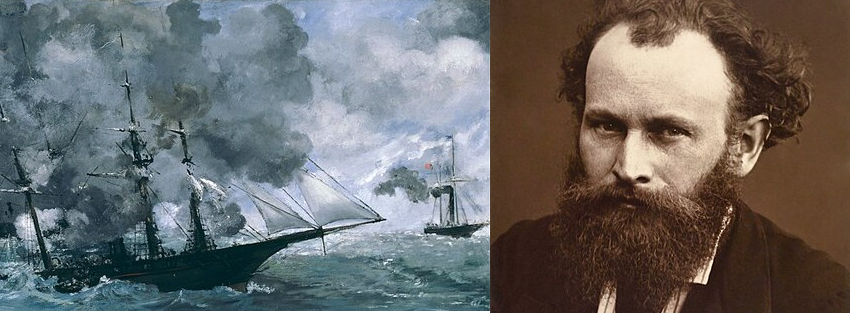

During the Franco-Prussian war everyone in Paris, whether painter, poet, or plumber, was swept up by history. Even after the abdication of Napoleon III and the birth of the new Republic that Édouard Manet and his fellow Impressionists had long dreamt of, the armies of the “Government of Defense” continued to suffer defeat after humiliating defeat across French territory. By the autumn of 1870, there seemed little hope of stopping Prussian forces in their relentless drive towards Paris.

The Siege

As bad news continued to flood in, many Parisians – if they had the means – fled from the city. Monet, who had a military exemption purchased by his father, headed north — crossing the Channel to London. There he was joined by Camille and their son where a small artists community of exiles was forming. Pissarro (who was technically a Danish citizen) came with his family, then Sisley, Daubigny, and their art dealer Durand-Ruel. Cezanne headed in the opposite direction — home to the south of France — to avoid being drafted.

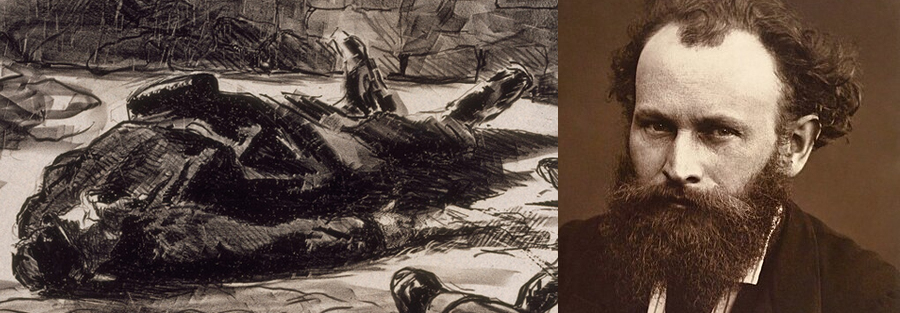

1870 Paris: Manet (left) in Bazille’s studio/Bazille in uniform

Manet and Degas, however, stayed to defend their city. Partisans of the new French Republic like so many of their friends, they enlisted in the National Guard. Renoir joined the cavalry. Rodin was drafted but later dismissed because he was too nearsighted. Gauguin served in the French navy in a group that captured four German ships. Frédéric Bazille, a close friend of Monet and Renoir, was killed leading an assault on the Prussians 65 miles south of Paris. Corot, in his 70s, refused to leave his studio and donated huge sums to the poor of Paris. Courbet, Gustave Moreau, Fantin-Latour, and Daumier also remained. Berthe Morisot, who could have spent the war far from the fighting with her sister in Normandy, insisted on staying with her parents in the city’s affluent neighborhood of Passy.

As the Prussians drew closer, the battered, retreating French armies, along with farmers from the countryside, poured into Paris. The population of the capital grew rapidly – just as the new Republican government was struggling to figure out how to feed a city about to be cut off from the outside world.

The Siege of Paris began in mid-September 1870, less than two months after the war began. The overwhelming confidence at the beginning of the war had now soured into fatalism. While the defenders had many new recruits, one general said, “We have many men, but few soldiers.” The Prussian armies systematically surrounded the city and began choking its life out.

Manet was stationed on the ramparts during the Siege, sleeping on straw whenever he had the chance. He wrote to his wife:

I hope this letter will reach you. . . Paris is determined to defend itself to the last and I think their audacity will cost them dearly…. I was on guard at the ramparts yesterday and the day before. We heard the guns going all night long. We’re all getting quite used to the noise….

Much to his chagrin, his commanding officer was Ernest Meissonier, an academic artist celebrated by the Salon, whose work he despised. Meissonier, in turn, refused to acknowledge Manet as a fellow artist – even though he certainly recognized him and knew his work.

Meissonier, Napoléon III at the Battle of Solferino, 1863

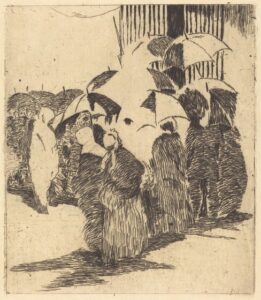

Understandably, Manet (like Degas) did little work during this period. He had closed his studio and removed his paintings when the German bombardment began. But, inspired by Goya’s great print cycle “The Disasters of War,” he did one small etching – Line in front of Butcher Shop. What looks at first like a pleasant depiction of city life in the style of Japanese prints is in fact a visual record of Parisian women trying desperately to get food because their families are starving. Manet wrote,

[The] butcher shops open only three times a week, and there are queues in front of their doors from four in the morning, and the last in line get nothing.

Manet, Line in Front of the Butcher Shop, 1870

Nearly lost in the pattern of umbrellas is the only hint that we are witnessing a scene of panic — a soldier’s bayonet poking up at top center. The soldier is there to keep the crowd from getting out of control.

Even in her fashionable neighborhood, Berthe Morisot suffered during the Siege. Like so many others in Paris over those long four months, she became seriously ill, faced artillery bombardment, a bitterly cold winter (the Seine was frozen for three weeks), and near starvation. All across the city, citizens burned whatever they could find to keep warm. With little food left in the city, Parisians turned to the Zoo for meat. Pets were eaten, then rats. The guns that had been so proudly exhibited by the Germans at the 1867 Paris World’s Fair now bombarded the city day and night.

The French surrender

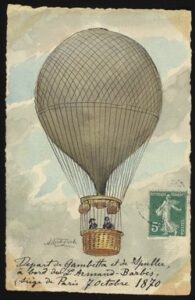

October 1870 – Léon Gambetta flees.

In October, the Minister of Interior escaped Paris by balloon. At the end of November, Manet, now an officer, fought in one last attempt to break the Prussian siege. Known as “The Great Sortie from Paris,” the Battle of Villiers was a disaster. Amidst flooding and bitter cold, the French lost 5,000 soldiers and retreated the eight miles back to Paris after only five days.

With winter setting in and Paris starving, the National Government could see no alternative to surrender. On January 26, 1871, France agreed to a ceasefire and an armistice with Germany. As part of the agreement, the Germans were given Alsace-Lorraine, the historically French territories west of the Rhine.

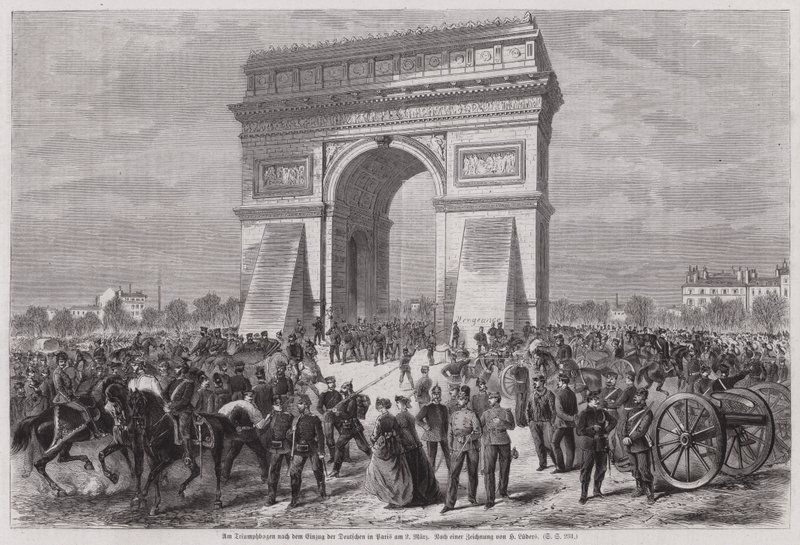

German Soldiers at the Arc de Triomphe, Paris, 2 March 1871

With the German guns finally silent, Manet and Degas, like many other Parisians, left the wounded city for the French countryside. On March 2, the French nation suffered the humiliation of seeing the German armies marching victoriously down the Champs-Elysees and through their Arc de Triomphe.

Civil War: The Commune

But peace did not last long in Paris. The treaty with the Germans was considered treachery by the local defenders, who refused to accept defeat or turn over their arms and cannons to the National Government. Instead, they formed a local governing body which they called “The Commune.”

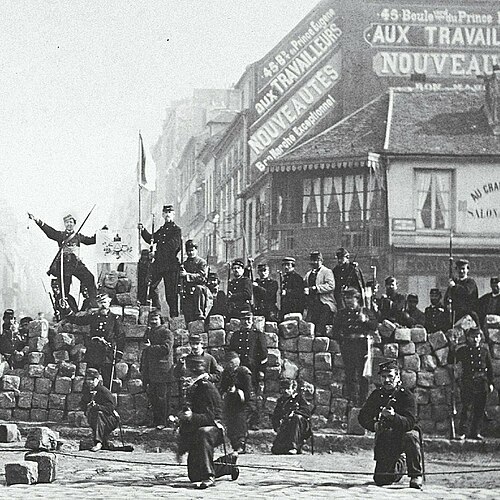

Barricades, March 18, 1871

Battles broke out in the streets — a civil war between the French military desperately trying to keep control and the local National Guard, radicalized by the war and supporting the new revolutionary city government. Barricades were raised all over the city.

The French national government in response ordered their troops to retake control of the city. But many soldiers, already convinced of the incompetence of their generals, refused to fire on their own countrymen. Rather than pointing weapons at the rebels, soldiers stripped off their uniforms and joined the rebellion. In one incident, rather than following orders to fire on a crowd, they shot the generals. After dragging them into the gutter, citizens took turns peeing on them. Control of the city by the federal government quickly began to collapse. In a few days, the local forces succeeded in raising the red flag of the Commune in public buildings all over the city. The humiliated remnants of the French national forces had no choice but to leave the city.

In the minds of the French government, now headquartered in Versailles, this was only a temporary tactical retreat. Declaring an independent Paris unacceptable, plans were made for an assault by French forces on its own capital. The Communards were open to a negotiated settlement, saying their goal was not an independent state but some degree of self-rule.

The government response was swift and deadly. Cracking down on the rebellion, the army turned their cannons on Paris. The first bombardment hit the western side of the city, not far from Berthe Morisot’s family home.

Manet, now in southwestern France, was horrified to learn what his long dreamed of French Republic had devolved into. He wrote bitterly to his fellow artist Félix Bracquemond, about their “unhappy country” and “the appalling depths to which we have fallen.”

The battle for Paris

The Communards had spirit but were never an effective army. A band of independent thinkers of many political flavors who shared mistrust of any central control, they chose to fight when and where they saw fit. Their leadership style was characterized as “perpetual improvisation.”

Yet, even though outnumbered five to one, the ragtag worker army ended up being more effective fighters than the regular, conscripted government soldiers. They were inspired not only by their cause, but because they were defending their homes and families. Sadly, their heroism and tenacity only resulted in adding more weeks to the months of destruction in Paris.

Notre Dame in flames, April 15, 2019

To get some sense of what Parisians suffered during this period, think back to the shocking scenes from 2019 when Notre Dame Cathedral was burning. As upsetting as the damage to that iconic, beautiful landmark was, it was only one building. That single disaster cannot compare to the devastation of Paris during the Terrible Year — first in the futile war with Prussia and then at the hands of the French military.

French guns pounded the city for weeks, even hitting their own Arc de Triomphe several times. The Palais de Justice, the Palais-Royal and the Hotel de Ville were turned into rubble. The Barbizon painter Millet wrote, “Isn’t it frightful what these wretches have done to Paris? Such unprecedented monstrosities make those Vandals [who sacked Rome] look conservative.”

Burning of Tuileries Palace (Louvre at top), May 23, 1871

The Communards themselves set fire to the Tuileries Palace, directly across from the Louvre. Once the magnificent residence of French kings and Napoleon, it burned for two days and became a pile of smoldering ruins. Today, only its famous gardens remain.

The Louvre, too, ended up in flames. Its priceless art collection survived only by luck, when a heavy rain put out the fires. Sadly, its library and the adjacent Finance Ministry were destroyed.

Finance Ministry, 1871

Most civilians were trapped in their homes by the bombardment and fighting in the streets. In April, when a delegation from the Commune pleaded with the leader of the French government for mercy, President Adolphe Thiers answered, “A few buildings will be damaged, a few people killed, but the law will prevail.”

Thiers had once been a radical journalist but, not surprisingly, was now detested by most Republicans. Flaubert in a letter to George Sand called the President an “abject pustule.” Manet referred to him as “that little twit” and proof that France was ruled by “doddering old fools.”

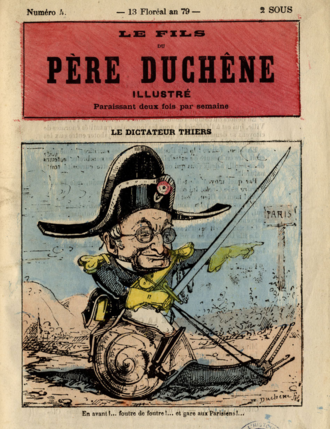

Thiers mocked in a Commune newspaper. “Forward! F**k of a f**k, and watch out for Parisians!”

As the battle for Paris dragged on, fires burnt throughout the city’s center, destroying thousands of homes. Berthe Morisot’s mother wrote:

Paris is on fire! This is beyond any description…A vast column of smoke covered Paris and at night a luminous red cloud, horrible to behold, made it all look like a volcanic eruption. There were continual explosions and detonations…It is unbelievable, a nation destroying itself!

By May, starvation and illness were rampant – just as they had been during the Prussian Siege. Added to these miseries were the vicious reprisals by both sides.

The last week of May would become known as “the Bloody Week.” Government firing squads and civilian vigilantes roamed the streets, conducting executions all over Paris. Suspicion ruled – suspected spies were dragged away and shot without trial. When it was rumored that women were firebombing buildings, the federal forces began shooting any woman seen carrying a bottle on the street. The Archbishop of Paris, who had organized relief for his city during the Prussian siege, was arrested then shot by a Communard firing squad. In one day, the French army rounded up hundreds of rebels in the beautiful Luxembourg Gardens and executed them. Degas’s father wrote to him “one had to climb over [bodies] in order to walk down the street.”

Commune barricade defended by women soldiers

Using guerilla tactics, Communards fought neighborhood by neighborhood against government forces. But they were outgunned and finally overwhelmed. After weeks of street fighting, on May 28th, the French army forced the surrender of the last holdouts in Montmartre – where the uprising had begun. The civil war and Bloody Week were finally over. It is estimated that as many as 30,000 Parisians died during these final months of unrest.

Paris after “The Bloody Week”

Manet was back in Paris when the Commune surrendered. He had returned from the Pyrenees to join the Communards in the final struggles against the French army. As Manet wrote to Morisot, even with all the destruction and suffering, he had found it “…impossible to live elsewhere.”

End of Part Two

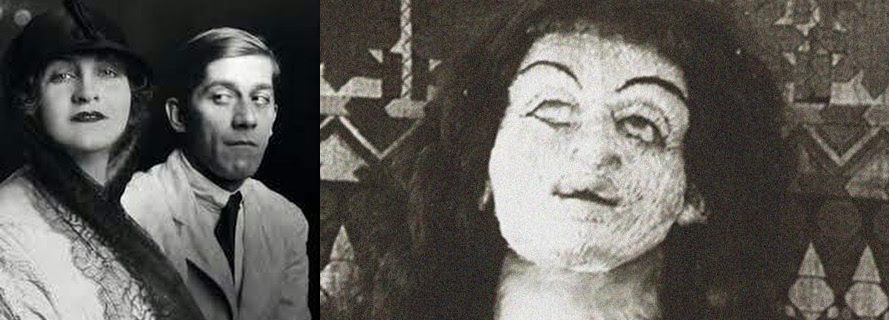

A strange, life-size doll is at the center of one of the Modern era’s most bizarre episodes. Its inspiration was the sudden end of an intense love affair between the Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka and the fascinating Alma Mahler.

A strange, life-size doll is at the center of one of the Modern era’s most bizarre episodes. Its inspiration was the sudden end of an intense love affair between the Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka and the fascinating Alma Mahler.

Marie Louise Fuller was born in 1862 on a farm outside of Chicago. As a young girl, she was inspired to be an actress by

Marie Louise Fuller was born in 1862 on a farm outside of Chicago. As a young girl, she was inspired to be an actress by

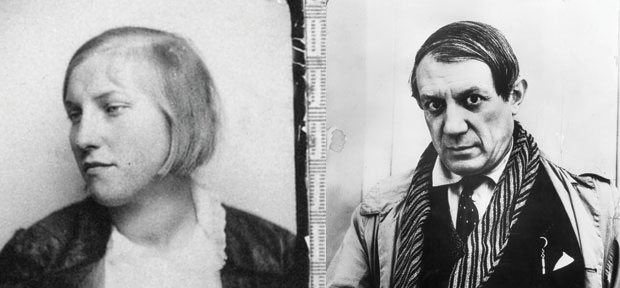

As the sun set in Paris, on January 8, 1927, Pablo Picasso was walking past a fashionable department store when his eyes fell upon a young shopper. Immediately infatuated, the artist (then unhappily married and in his mid-forties) took Marie-Thérèse Walter by the arm and said, “I’m Picasso! You and I are going to do great things together!” She was confused by the man and unaware of who he might be. Picasso introduced himself by dragging her into a bookshop and showing her a book filled with reproductions of his paintings. Thus began a passionate affair and an enormously productive period for Picasso.

As the sun set in Paris, on January 8, 1927, Pablo Picasso was walking past a fashionable department store when his eyes fell upon a young shopper. Immediately infatuated, the artist (then unhappily married and in his mid-forties) took Marie-Thérèse Walter by the arm and said, “I’m Picasso! You and I are going to do great things together!” She was confused by the man and unaware of who he might be. Picasso introduced himself by dragging her into a bookshop and showing her a book filled with reproductions of his paintings. Thus began a passionate affair and an enormously productive period for Picasso.  Volume 2 of our series “

Volume 2 of our series “